Review: Wege der Moderne: Josef Hoffmann, Adolf Loos und die Folgen. Museum für angewandte Kunst, Wien, through April 19, 2015.

I]

Die Kunstwissenschaft beginnt zu entstehen und hat bald die naïve Zeit in ihren Bann gezogen… Die Folgen sind verheerend.

Art History has started to assert itself; already our unsuspecting age is drawn into its wake… The consequences are devastating.

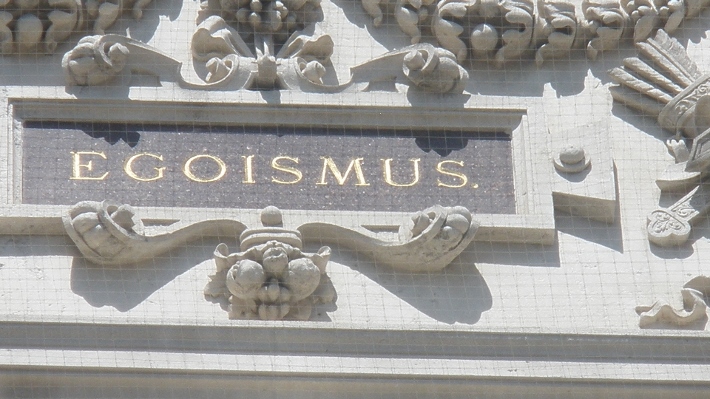

Either someone at MaK (the Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna's Museum of Applied Arts) has unsuspected depths of humor or, to paraphrase something Lenin said of Trotsky, the curators' self-satisfaction is so great that it amounts to a kind of objectivity: the quote above is from the Jugendstil designer Josef Hoffmann; it's a critique of the great late nineteenth century architect Otto Wagner who, though not a modernist himself, left an indelible mark on Modernist Architecture. In this show the theoretical tensions between Hoffmann and Wagner make up two sides of a fruitful triangle that connects Wagner, Hoffmann and Adolf Loos, the great Viennese Modernist. Unfortunately, the curators have inserted themselves so clumsily into the discussion that the exhibition ends up as a pile of interesting objects connected by weasel-signage.

The show has five sections, three of which have nothing to do with its theme; the first consists of late nineteenth-century gewgaws: Bohemian knockoffs of Wedgwood Blue and such; the fifth includes, among other items, a copy of Duchamp's bottle rack. (For some reason there's no Warhol print.) The second, third and fourth are devoted to Wagner, Hoffmann and Loos, disrespectfully.

I say "disrespectfully" because there is nothing in the objects shown that justify the curator's mendacious thesis, as presented in the introductory signage:

Für den modernen Konsumenten entwickelten [Hoffmann und Loos] zwei gegensätzliche Wege Individualität und Selbstverwirklichung [authenticity] zu entfalten…: Bilder moderner Lebensweisen des emanzipierten Bürgertums.

For the benefit of the contemporary consumer [Hoffmann and Loos] developed two opposing methods to encourage Individualism and self-authenticity: visions for the modern lifestyle of the emancipated bourgeoisie.

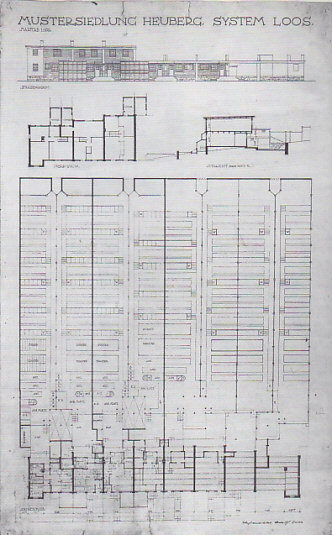

That's pretty funny when you consider that the objects meant to illustrate the "visions for the modern lifestyle of the emancipated bourgeoisie" include a scale model for the Kirche am Steinhof, a church for the patients in a mental institution on the edge of Vienna; or a design for a low-income housing project that Loos executed as Head Architect for the City of Vienna under the Austro-Marxists in the 'twenties. Not malcontent with finding objects illustrative of their thesis, the curators engage in a kind of consumerist So's-Your-Mom attack involving out-and-out rants against those items that happen to contradict their thesis, meaning a fair proportion of the items on display; which begs the question: if the objects are such strong disproofs of the curatorial thesis, then why show them?

Curators are entitled to their pet theories; they're entitled to choose whatever objects they wish to illustrate their theories; they're not entitled to whatever factoids they chose to make up: here is the signage for the section on Loos and social housing:

Curators are entitled to their pet theories; they're entitled to choose whatever objects they wish to illustrate their theories; they're not entitled to whatever factoids they chose to make up: here is the signage for the section on Loos and social housing:

Ab 1924 baute die sozialdemokratische Stadtverwaltung allerdings vorwiegend innerstädtlische Geschoss wohnbauten statt emanzipatorischer Siedlungsprojekte.

Beginning in 1924, however, the social-democratic city government built almost exclusively multi-story residential buildings in the inner city instead of emancipatory projects.

Even in German, a language that allows for great condensation of meaning, it would be hard to fit so many misstatements in one short phrase. The authors want to persuade us that Loos's earlier low-income projects for the City of Vienna, because they were built on the edge of the Vienna Woods, were the equivalent of the "emancipatory" garden cities built as early as 1898—and not 1910 as they claim earlier on. Their reference to the "inner city" confuses Vienna's Inner City (the First District) with any and all urbanized or semi-urbanized areas in which the City built: the Austro-Marxists, who were less interested in the size of buildings than in the dispersal of low-income housing, built in all sizes throughout Vienna. To prove their point the curators follow up with a drab model of Loos's unrealized Terrassenhaus project of 1924 which does, indeed, look like someone's idea of workers' housing in East Germany unless the visitor happens to know that the Terrassenhaus was planned as a form of low-density housing, and was to have gardens on each of the terrasses. (Terrassenhaus. Get it?) To top it all, the curators seem to be unaware that Loos's design is based on an earlier design for his friend Gustav Scheu, who had attempted to bring the original, English, inspiration for the Garden City to Vienna—hardly the black-and-red contrast they fantasize. Eve Blau demolishes the curators' manichean assumptions much better than I can—and with far more authority:

The fantasy that low-income housing must be rural and non-communitarian in order to be emancipatory comes straight out of fascist architectural theory; the similar illusion that only single-family houses are emancipatory is straight out of the manure-pile of late capitalism. In Austria, even today, there's little difference between the two.

Further on, as one of the curators explains,

In einem… Kontrastpaar…stellen wir auch zwei Frauenbilder einander gegenüber. Das eine ist die Wohnung für die alleinstehende, berufstätige Frau von Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky von 1928. Gegenübergestellt is das Boudoir für einen grosssen Star von Hoffmann, gezeigt 1937.

In a contrast of opposites…we also placed two women's visions next to one another. The first is the Apartment for an Independent Professional Woman [designed by] Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky in 1928. Next to it is the boudoir designed by Hoffmann in 1937 for a famous star.

I should explain that the Austrian political system (hence the cultural system) still follows a curious arrangement called the Proporz: if two gay women are kicked out of Café Prückl across the street from MaK for tongue-kissing it is incumbent for the Minority Party to have its say about tongue-kissing lesbians in cafés. The same goes, apparently, for museum exhibitions. Schütte-Lihotzky presumably belongs to that "collectivist orientation of the age of dictatorships (kollektivistischdenkenden Zeitalter der Diktaturen)" during which, the curators conclude, "gerieten die individualistischen Denkweisen von Hoffmann und Loos in vergessenheit. (The individualistic philosophies of Hoffmann and Loos were consigned to oblivion.)" For every woman architect who designs oppressive efficiency apartments for lonely professional women there has to be an empowering boudoir.

II]

There are two problems with the curators' thesis, one mere ineptness, the other more troubling. As to the first: if you're going to make this kind of blanketing, langue-de-bois argument about individualism and collectivism don't use Viennese architecture to make your point because Viennese spatial thinking for the past hundred-twenty-five years has consistently fostered a conception of public and private space that doesn't fit the expected pattern: take one look at Wagner's Majolica House, for instance:

in which the decorative, flattening elements are turned inside out to face the public space—now that would have made for an interesting contrast with Loos's ideas about ornament, nicht wahr? And, if you're going to make those kinds of arguments don't use architecture at all because there is no possibility of excluding the "collective" from architectural theory. This exhibition does perfectly well when it limits itself to the decorative arts alone: Hoffmann's chairs, Loos's designs for drinking glasses: stuff that was marginal to Wagner's work, and Loos's, though not to Hoffmann's.

That raises the second question: why would anyone so desperately want to exclude the so-called collectivist idea from discourse that they'd devote a whole show to do so, the museological equivalent of a creationist amusement park? Come to think of it, why does Merkel reject the Greek bailout plan? And why do cats lick their balls? Answer: Because they think they can. In the cat's case they may actually succeed.

Vienna, my Viennese friends keep reminding me, is a place like any other at the edge of the Great Global Tsunami. As I keep reminding them in return, the first step in resisting Globzilla is to understand the local peculiarities of resistance. Henry-Russell Hitchcock, the architectural bouncer at the Museum of Modern Art, had good reasons to keep the Viennese tradition out of his narrative: "From the first its significance was more political than architectural," meaning it didn't fit into the Modernist Formgeschichte. The Museum für angewandte Kunst is a fine illustration: one of the earliest museums devoted to the formation of a productive work force in the areas of culture and design, it's been turned over the past decade into an educational tool for the formation of consumers.

This show goes even further. It does not merely glorify consumerism for the benefit of the visitor, it attempts to impose consumerism as an ideology, and to impose it on the whole of the History of Art. The sociologist Zygmunt Baumann has written of the "flawed consumer" meaning the citizen who makes the wrong choices (or makes no choice at all) "in a society of consumers, in which life-projects are built around consumer choice rather than work, professional skills, or jobs." The flawed consumer is the usual object of the tender ministrations of the Global Museum. Instead this show addresses that bugaboo of art schools and Art History Departments everywhere: the flawed cultural producer.

It's no secret to anyone by now that museums, like all educational institutions under capitalism, have a "hidden curriculum:" the form appears to be the conveying of empirical data or of more-or-less scientifically valid information; the structure is best represented by the fact, obsessively mentioned by all well-thinking critics, that the gift shop is strategically placed at the exit of the exhibition. However, over the past ten years we've seen a sea-change in the art schools and the Art History departments: it's not simply that they teach capitalist relations of production as the form under which all education must be provided: free-market capitalism has become as well the exclusive content of the curriculum as well. I have taught (or rather, tried to teach) at an art school called the School of Visual Arts where every lesson, every apprenticeship, is a lesson in identifying that which supposedly sells. I have sat in seminars with full art history professors at real universities who insist that the History of Art is equivalent to the History of Masterpieces, and the definition of Masterpiece is "object inevitably bought and commissioned by the very, very rich, yesterday, today and always"—Alois Riegl would be spinning in his grave. The History of Art is now presented as a Konsumentgeschichte in which artists are valid only to the extent that they're in perfect congruence with the inevitable march of the Market: The history of all hitherto preceding culture is the history of consumerism. By now all of American education, with Europe closely following suit, has become vocational education; the only possible vocation is consuming, and it's taught with a dogmatic rigidity that would turn Lysenko red. Except, how is the museum visitor expected to learn to consume correctly when it comes to architecture? Will they be selling community housing in the gift shop? All this explains the curators' stridency, their rage against Loos and Wagner and Schütte-Lihotzky in particular. They seem less interested in finding the unfindable than in turning their audience away from what's clearly to be found in Wagner, Loos and others. It’s the rage of the capitalist Caliban at not seeing his face in the mirror.

To be fair, I should be writing "one of the curators;" this show, like a few others I've seen around Vienna, falls into the category of behavior the French call "drowning the fish:" it's as if one of the participants were working to drown out the other's message, or the message of both. And perhaps I shouldn't be blaming the curators at all, since European culture at this juncture is under intense pressure from its unelected Herrschaft, the European Union, a gigantic insect working to impose its values from above. Still, one has to wonder how many museum visitors are impressed by this type of propaganda: it reminds me of the old rule that you only turn negative in a political campaign if you're slipping—and the Union, obviously, is slipping badly. Frantz Fanon, in writing of the culture of the colonized, argued that the colonizer doesn't really care whether the colonized have a past, only that they have no future. Wagner, Loos and Schütte-Lihotzky and the others: this is the future the EU would like you not to have. A good enough reason to visit.

- Wöfflin Jack

February 23, 2015.

subscribe:

Like an RSS feed or Twitter, only easier: you drop me a no te and every week or so I send you a short message with a link to my latest posting; other stuff, maybe every other month.

donate:

Because paying no dues to Caesar is the one luxury that's not encouraged in a consumer society. Easy: you paypal me a buck or two.

comments:

And you don't have to sign up to post them; they are moderated, though.