WOID XXII-03.

WOID XXII-03.

[Just a finger exercise in training for my upcoming talk—excuse me, Lectio Magisterialis—at Macro Asilo in Rome, December 1.]

On August 22, 1792, only twelve days after the Royal Swiss Guards had been massacred in the courtyard of the Tuileries and the last king of France deposed, the revolutionary deputy Pierre-Joseph Cambon proclaimed:

"We must preserve the monuments of art, we must preserve them to serve as models for those monuments to freedom that remain to be built. We must preserve even those images… that will forever deserve our gratitude for having made us hate kings... Let us bring them together in one place to form the Museum [of the Louvre]."

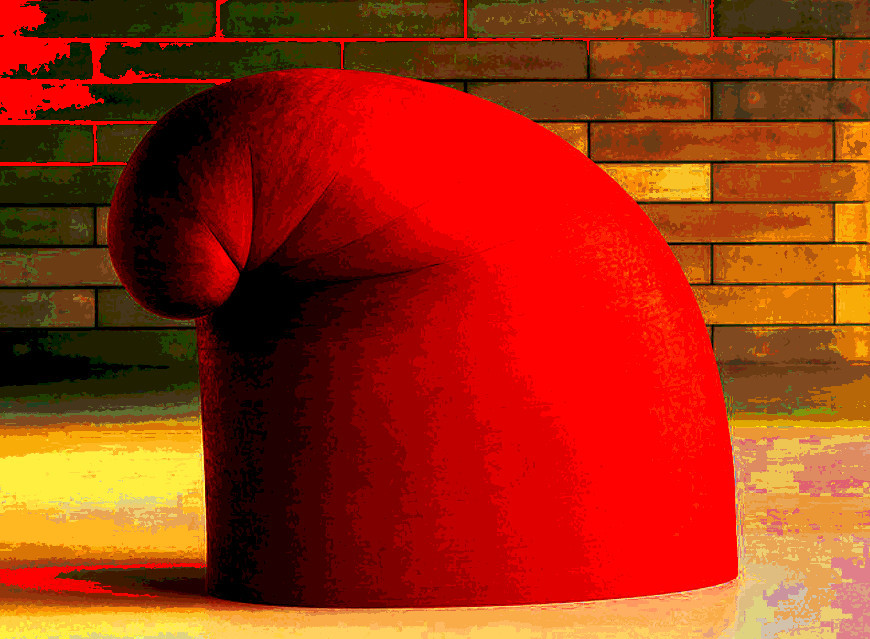

Mission accomplished, Citoyens. Just as the monuments of tyranny once found a home in the Louvre in Paris, so, too, Big Phrygian, Martin Puryear’s monument to revolution, has found a home in the abode of the oligarchs, the Glenstone Museum set to reopen October 4 outside of Washington, DC. Actually it's been given its own crafted jewel of an architectural display in the Glenstone's two-hundred million dollar new building. Was ever sans-culotte so pampered?

Either the owners of the Glenstone Museum are secret emissaries of the Revolution, or they’re as stupidly insouciant as the powdered noblemen of 1789. Puryear’s large-scale sculptures are elegantly crafted of select and polished materials. In the style of Giacometti at his best they balance and blend references from non-European cultures with a focused attention to form. They remind me of those deceptively simple objects of Native American use whose every inch of surface seems reduced to its essentials through meaningful use. One British critic calls Big Phrygian “elegant and enigmatic.”

Yeah, right. Big Phrygian is an unescapable allusion to the Phrygian cap originally taken by newly liberated slaves of the Roman Republic. Coming from an African American artist with a deep sensitivity to the cultural nuances of form, Big Phrygian blends the European struggle and that of the African Diaspora into one: the cap worn by the French revolutionaries was associated as well with the liberation of Haiti, whose arms are still surmounted by the same bonnet. Associated, also, with the liberation of American slaves: a statue of Liberty bearing a Phrygian cap was once banned from the dome of the Capitol on orders of then-Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who explained that “American liberty is original and not the liberty of the freed slave." That was not merely a distinction based on color: The American elites have long nurtured the fantasy that “American liberty” had been attained in a gentlemanly manner, as opposed to the freedom of the French or Haitians, won through blood and massacre. The fear of violence hovers over the symbol of the Phrygian cap as it once haunted the nights of American slave owners, and this is what gives Big Phrygian its tension of signification and form, an image made to make us hate tyranny, and probably rich bastards as well, as smoothly honed as the blade of a guillotine.

Between the wealthy Art-lovers and the French revolutionaries, there is a major difference, however. The French revolutionaries attempted to suppress or displace the use-value of the “playthings of tyranny,” either by destroying monuments and artworks altogether, or by reclaiming what they wished to be their proper use, changing the function of art object from monuments to tyranny to reminders and lessons about tyranny in an “activation of meaning;” whereas the last thing the owners of the Glenstone have in mind is teaching about tyranny. “Look — really use your eyes,” says Emily Wei Rales, current patron and a former curator and gallery director. “Allow that to be your primary experience.” Which begs the question, if all that’s needed is to “really use your eyes” why has the Museum hired and trained 24 guides for an expected 400 visitors a day? To make sure the visitors don’t use their brains? One can't help wondering: is the new museum the excuse for the art, or vice-versa?

I hate to be in any form or fashion in agreement with Senator Orrin (“Booby") Hatch, let alone Charles (“Eating-up-the”) Grassley, both of whom have been ruthless in policing tax scams by private museums. (Tax scams by farmers and churches, not so much). The issue is whether the Glenstone is making itself sufficiently accessible to the public, since accessibility to Art is supposed to be in the public good. Personally, it would give me the greatest pleasure if Big Phrygian were to be sent on tour, say just North to some of the rougher areas of Baltimore; or if busloads of minority kids were brought in to discuss the meaning of Big Phrygian. (I suspect the artist would get a kick out of it as well.) I can't imagine the part about Haiti and the guillotine will be discussed, however.

And this, too, is where the Jacobins and the oligarchs diverge. Cambon was a smart financial mind, the head of the Finance Committee of the National Convention. Cambon saw the arts as productive capital because they taught the people, and socially productive because of what they taught, which was hatred of tyranny. The Rales don’t think art can be socially productive, just "inspiring" in some vague, undetermined way, the more undetermined the better. The “educational mission” of the Glenstone Museums is merely the means to justify the "public utility" of the investment, and the productive investment isn't the art itself but the new building that houses them: after all the investors could have got the same break on the art itself simply by donating their artsets to another museum. The big money's in new construction and maintenance, which have the immense advantage over mere passive assets like artworks, that they offer continuous opportunities to claim deductions. Like all investments, Art is supposed to produce value for its owners, not merely preserve it, and there are myriad ways to produce value, so it’s unfair (or rather, disingenuous) of the New York Times to suggest that the Rales are among those “wealthy people” who avoid taxes by “deduct[ing] the market value of any art, cash and stocks they donate to their museums or foundations” The Rales' productive capital is not vested in the artworks themselves but in the fantasy of the museum’s capacity to attract visitors and convince them that “Art” in the abstract is in the public good, the more abstract, the better. And its investment value is, that it’s worthy of a tax break because showing it is in the “public interest.” That's why, at this point in time, there's more museums being built than there are artworks available to fill them. The Phrygian bonnet's just an afterthought.

To quote another French revolutionary:

“It is impossible to arrange for what has been to not have existed. Preserve, republican Frenchmen, preserve the memory of these monsters, the better to abhor them.”

In America today it is perfectly possible to arrange for what has been to not have been, provided you’ve got the schlitz—what else are universities and museums for? Arguably the French revolutionaries engaged in destructive vandalism. The owners of the Glenstone Museum, like most art folks today, have invented a new category, Discursive Vandalism: there is no activation of meaning at the Glenstone, or in most American private museums, only the desperate attempt to suppress meanings.

In the days leading up to the French Revolution the powdered noblemen would turn up to applaud Beaumarchais's Figaro, especially the part where the hero addresses his audience and denounces their own privilege—how could it apply to them? Let’s hope the same will be said some day about Big Phrygian. Marx, I hope so.

October 12, 2018