WOID XXI-50

Review: Kuhn,

Gabriel//Deutsch, Julius. Antifascism, Sports, Sobriety. Forging a

Militant Working-Class Culture. Edited and translated by Gabriel

Kuhn. Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2017.

On January 9, 1968 an officer for French intelligence services reported that the Minister for Youth and Sports had been accosted the previous day by a group of radical students outside the new university complex in Nanterre. When the Minister attempted to dialogue one student, identified as “M. Marc Daniel Kohn-Bendit,” informed the Minister that “the establishment of a sports center was a Hitlerian method... to draw young people to Sport in order to distract from real-life problems.” In his usual chameleon style Cohn-Bendit was echoing arguments that had divided the Left in the interwar years, no more so than in Red Vienna, that short-lived, extraordinarily productive period of Socialist experimentation that lasted from 1919 until its destruction by fascist forces in 1934. In its farcical, stumbling way, the exchange between the hipster and the minister echoes earlier, far more sophisticated disagreements between the likes of Wilhelm Reich, the brilliant, erratic psychoanalyst and proponent of the concept of “self-regulation”, and the top leadership of the Social-Democratic administration of Red Vienna who were concerned that the evolution and even the survival of the Socialist experiment were endangered by the working class’s lack of discipline in areas of corporal behavior, alcoholism, workplace organization and, of course, Party discipline. This is more than a coincidental convergence since Cohn-Bendit’s screed owed something to the critique of Administered Culture that originated in Vienna, Budapest and Frankfurt in the years after World War I and was taken up again in 1960s France. (Another participant in this debate, Ernst Fischer, is known to art historians for his classic overview, The Necessity of Art.)

In Vienna the contradictions of a proletarian culture imposed from above were glaringly exposed on July 15, 1927, when a spontaneous uprising outside the Palace of Justice was brutally suppressed by the Police and State and the Social-Democratic leadership held back their own militia, the Republikanischer Schutzbund. In the following years, as the Austrian Government progressively tightened its noose around Red Vienna, the increased imposition of Party discipline further alienated the Social Democratic leadership from its base. One by-product was the flourishing of massive public events which, it has been argued, merely intensified the symbols of proletarian unity while acting, not as preparation but as substitutes for actual organized resistance. Matters came to a bitter head on February 12, 1934, when the long-expected military assault on Red Vienna was met with a resistance hopelessly disorganized, in part because its top-down command system had been wiped out and perhaps as well because any type of spontaneous resistance had long been discouraged. Red Vienna collapsed amidst desperate street fighting while its leaders fled to Czechoslovakia.

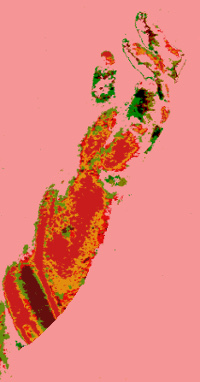

Julius Deutsch was one of those leaders. Born in 1884 in what is now Western Hungary, Deutsch rose from printer’s apprentice to Doctor in Law under the sponsorship of the Austrian Socialists. In the last days of World War I, during the transition from War Socialism to Socialist Governance, Deutsch was charged with smoothing production and supply problems between workers and the Army. After the Fall of the Hapsburgs he became Minister of Defense. From 1918 on he organized the Volkswehr, the “People’s Militia,” which eventually morphed into the Schutzbund, of which he remained the commander until 1934. In 1926 Deutsch assumed the Presidency of the Austrian Worker’s League for Sports and Body Culture (Arbeiterbund für Sport und Körperkultur or ASKÖ) and a year later the presidency of the Socialist Workers' Sport International (Sozialistische Arbeitersport Internationale, or SASI). In the years that followed SASI achieved enormous international stature, culminating in the Workers Olympiads of 1931 which attracted a larger audience and a larger group of athletes to Austria than the bourgeois Olympics would bring to Los Angeles and Lake Placid the following year.

When researching Red Vienna it helps to begin with Helmut Gruber’s bitter, dismissive survey, Red Vienna. Experiment in Working-Class Culture 1919-1934 (Fortunately available for free download at https://libcom.org/files/redvienna.pdf). Gruber is what the French call incontournable, meaning his influence on historians runs so deep that no understanding of Red Vienna is possible without a thorough critique of his arguments and a review of his multiple, often misread, primary sources. Gruber’s overarching argument is, that the leadership of Red Vienna, by attempting to impose their own vision of culture on the Viennese Proletariat, effectively disempowered it, leaving it vulnerable to the fascist takeover. Here is Gruber’s take on the mass festivities accompanying the Worker’s Olympiad of 1931:

This and other celebrations… had a compensatory character for the actual political reversals of the SDAP [viz. SDAPÖ, Worker’s Social-Democratic Party of Austria]. They pointed to a future of success while leaving current events out of the picture.

Performers and audience intoning an oath in refrain had an exorcistic effect in which “the power of individual cognition was surrendered and the power of decision making reduced in favor of a romantic and emotional attachment to a value system."

Cohn-Bendit would have agreed; so would Ernst Fischer and Wilhelm Reich, both of whom were made aware of the powerlessness fostered among the working class by the Social-Democratic leadership after the massacre of July 15, 1927. The Mass Psychology of Fascism (perhaps Reich’s most influential book) originates in his intellectual exchanges with the leaders of Red Vienna over their demands for the “surrender of intellectual cognition.” Curiously, while Gruber freely applies his critique of disempowerment to the festivities of 1931, he can’t bring himself to apply the same critique to the actual sports component, the concurrent Worker’s Olympiads: the preceding pages, describing the impact of the Worker’s Olympics on Vienna’s political culture, are downright adulatory:

Even though the SDAP failed to turn worker sports into an institution for the political education of the masses or to transform a basically recreational activity into an instrument of class struggle, worker sports produced symbols of political importance. In addition to the obvious signs of discipline and orderliness, solidarity and community, the worker athlete’s body itself projected an image of power and control.

This begs the question: why do “obvious signs of discipline and orderliness” become symptoms of powerlessness when applied to a choral group, but not to a sports events? The ready explanation is that Gruber is recycling Vulgar Marxist categories: Culture is “superstructural;” therefore any appeal to revolutionary potential is a priori deluded; sports, supposedly, is not “superstructural.” Therefore ping-pong is the true expression of the People. By the same token, one may assume, Sports is a spontaneous expression of Proletarian Culture; choral singing, not. As to reading books...

The second explanation is, that like most historians of contemporary Austria (and most Austrian politicians as well) Gruber falls on the horns of Austrian particularism, whose particular distinction consists of defining the uniqueness of Austrian culture in terms and concepts borrowed from German History and Culture. (I have yet to read a mention from any historian that almost every one of the 89 civilians butchered on July 15, 1927, had a Czech or Polish surname.) Among historians of Red Vienna this “particularism” has the advantage of allowing them to apply to Austrian Social-Democracy the same criticisms that were directed at German Social Democrats of the inter-War years by the Comintern, irrespective of differences: social-traitors who diverted the working class from its mission, yadda-yadda. Any stick will do to beat a running dog.

Antifascism, Sports, Sobriety is slim and to the point at 114 pages. One half is given over to Kuhn’s own survey: background information on Deutsch, on militant activities, on Red Vienna. The rest is given over to three short extracts from the writings of Julius Deutsch, translated by Kuhn himself, while the Appendix covers a biographical section and a selected bibliography. This slim volume has none of the theoretical pretensions of a Gruber, it’s what’s academic reviewers like to call “introductory rather than critical.” Its second most useful feature is the raw information on the worker’s sports movement in the Interwar years, in the form of factual data and bibliographies: Red-Vienna-for-Dummies-who-are-primarily-interested-in-Sports. (The illustrations, pulled from contemporary sources, are a lot classier than the cartoons in the Dummies series.)

The book's most useful feature, however, is the three short selections from Deutsch’s own writings, translated with clarity and elegance by Kuhn himself. However, the three selections from Deutsch himself suggest a narrative at odds with the essay that precedes them. Kuhn’s emphasis on the intricacies of defensive tactics and military strategies evades the broader question raised in the subtitle of his book, “Forging a Militant Working-Class Culture” and raised in Deutsch’s own writings: what was the place of the movement for a progressive “Corporal Culture” within the broader cultural movement known as Red Vienna? And for starters, was Red Vienna's culture ever meant to be “militant,” let alone working-class in the sense of raw physicality? To quote Kuhn’s own introduction:

The book focuses on the physical aspects of workers’ culture because they have been the most neglected in historical accounts. There exist far more studies about worker’ education, literature, theater, and other intellectual and artistic pursuits than the physicality of the proletarian movement. The latter, however, was at the heart of the Austromarxist experience, not least because the ever-growing fascist threat it faced demanded physical defense.

To paraphrase the art critic Thomas Hess: “Culture is not War: there are no winners and no losers.” It’s not at all obvious that the “physical aspects” of worker’s culture have been “neglected,” or by whom, or how, or why that matters. It is not at all clear where the demarcation lies, or once lay, between “worker’s education,” etc. and the “physicality of the proletarian movement.” To argue as Kuhn does that “physicality… was at the heart of the Austromarxist experience… because the ever-growing fascist threat… demanded physical defense” is tacitly to endorse the Cold-War argument (propagated by either side) that “Democratic Socialism doesn’t work.” It’s a convenient argument for people like Gruber, who after the fall of the Soviet Union could switch camps effortlessly: from “Social-Democracy failed because it was bourgeois” (the Communist version) to “Socialism always fails because it’s utopian” (The Neoliberal version).

In a nutshell: is the expression “militant working-class culture” a contradiction in terms? The heart of the Red Viennese experience was not defense against the “ever-growing fascist threat,” much as one wishes in retrospect that it had been. It was the creation of the New Man, a term popularized by the Austromarxist philosopher Max Adler and possibly disseminated in 1960s France by Adler’s student Lucien Goldmann. It was this call to create a new type of individual within a new kind of culture, not the call to defend against fascism, that constituted the overarching unity of the culture of Red Vienna, a unity of purpose though not of method; a unity that encompassed a vast range of figures and positions, from psychoanalysts like Alfred Adler to educators like Otto Glöckel, health-care advocates like Julius Tandler, architects like Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and beyond, not to mention the temperance movements and the sports movements that are the focus of Deutsch’s own writings.

The three extracts differ markedly in tone, no doubt because each is aimed at a different type of audience. The last (“Class Struggle, Discipline and Alcohol”) is the most blustering, with its talk of class conflict and worker discipline. It was addressed to a worker’s temperance group. Oddly, this section comes last in the book, which would serve to justify the Gruberian argument that the ideology of Red Vienna became more intransigent as the leadership’s will to resist diminished, except the original was written in 1924, before the other two. The second extract (it comes first in Kuhn’s book) was published in 1926, and it announces the foundation of the Red Falcons, the left-wing youth group whose ambitions were closer to the Boy Scouts than to any liberatory movement: the Red Falcons integrated male and female teenagers under a call for clean living and sexual abstinence—a point of intense disagreement, notably from Reich. In addition, Deutsch’s text is contemporaneous with the Linz program of the Social-Democratic Party, which promised a greater reorganization of party activity on defensive lines and, most important, threatened a violent response to further fascist encroachment—a promise that proved to be empty within a year. Then again, Deutsch was no military strategist—in fact he was no military man at all, but an organizational bureaucrat. As this text makes clear, he had neither the intention, nor even the insight, to modify the military system of command to meet the need for offensive tactics.

Only the third passage in Kuhn’s book is directly related to Sports—it was originally written in 1928 and updated for the Worker’s Olympiads. Here, too, Deutsch is not primarily interested in the offensive potential of sports, in fact the reverse: by the early ‘thirties the Schutzbund had become an official part of ASKÖ, rather than the other way around. If there was any attempt at a Socialist Gleichschaltung it ran in the opposite direction of the fascist version: not of integrating a worker’s culture into greater militarization, but of integrating the defense against fascism into a worker’s culture.

Like other Red Viennese, Deutsch did not draw a distinction between corporal culture and intellectual culture. In one passage he tells with pride how the workers who visited Nuremberg for a sports event crowded the Albrecht Dürer Museum, whereas the Nazi athletes and their supporters stayed away. The argument takes on its full force in German thought, which since Kant has drawn a distinction between Kultur and Bildung on the one hand, and Zivilisation and Erziehung on the other: between Culture as an elite practice that is attained through elite formation of the “superior” classes, and Zivilisation, the day-to-day practice of a society develops through practical and moral education or Erziehung. Rather than exacerbating the Class Struggle the intellectual and political leadership of Red Vienna attempted a united front of bourgeois and working-class elements within what they imagined to be an already Socialist city, much as Bukharin advocated in the USSR at the time. For the Red Viennese it was understood that this front would foster the abolition of the distinction between Kultur and Zivilisation. Such elements are consistent with Deutsch’s argumentation, along with questions of worker autonomy, of self-discipline, of horizontal coherence. In every case the primary issue is not the defensive efficiency of practice, be it in the realm of abstinence, sports, or the youth movement: the issue is process of human relations involved in this particular conjuncture. The needs for self-defense are secondary to the formation of the New Man. Regrettably, Kuhn did not include a translation of Deutsch’s own pamphlet justifying the leadership’s failure to bring out their own militia after the massacre of July 15, 1927.

There’s a sweet moment toward the end of an old Hong-Kong Kung-Fu movie, I forget which. The scene is set at the end of the Opium Wars, and the virtuous Chinese hero is pitted against a double-dealing round-eyes whose own Kung-Fu skills are technically as good as his but whose moral and cultural development are no match. When Round-Eyes, in frustration, pulls out his colt the hero remarks: “Kung-Fu is no match for bullets.” It seems a bit much to blame the Austromarxists for their inability to build a new culture while fighting off the fascists. More to the point, it’s a bit Comintern to suggest that the Red Viennese failed to develop the resistance against fascism because they attempted to build a united front—or as they say at the Comintern, because they were "premature anti-fascists." Kuhn’s narrative of Austromarxism should be seen, like Kung-Fu movies, as a good-faith effort to confront historical loss with arguments that, as the Kung-Fu movie makes clear, may not be valid tools to deal with future struggles after all. The people of Red Vienna took seriously—perhaps too seriously—Marx’s in junction that "The working class cannot take hold of the state machinery and wield it for its own purpose," no doubt because the Soviet Union offered galling proof of that. To obsess about this apparent “failure to win” is not merely to relive a past that will not return, but to ignore differing circumstances, now and then. No doubt Kung-Fu’s no match for bullets. No doubt, as with sports, it has other uses….

But all of this is minor quibbling next to the clarity and elegance of Kuhn's translation, equal to the clarity and elegance of his previously published collection of extracts from the anarchist Eric Muhsam. At a time when several projects are underway to make available in English a greater proportion of Red Viennese literature, Kuhn's contributions are a blessing without disguise.

Paul Werner

Editor, The Red Vienna

Reader

March 13, 2018