Reviews:

- 150 Years of Gustav Klimt. July 12, 2012-June 1, 2013. Schloss Belvedere.

- Klimt up close and personal. Images ― Letters ― Insights. Through August 27, 2012. Leopold Museum.

- Gustav Klimt. The Drawings. Through June 10, 2012. Albertina.

- Gustav Klimt: Expectation and Fulfillment. Through July 15, 2012. MAK.

- Emilie Flöge's Collection of Textile Samples. Through October 14, 2012. Volkskundemuseum.

- Against Klimt. Nuda Veritas and her Defender Hermann Bahr. Through October 29, 2012. Österreichisches Theatermuseum.

- Klimt. The Wien Museum Collection. Through September 16, 2012. Wien Museum Karlsplatz.

- Without Klimt. Gustav Klimt and the Künstlerhaus. July 6 through September 2, 2012. Künstlerhaus.

- Installations by Gerwald Rockenschaub and Susan Philipsz. Through January 1, 2013. Secession Building.

- Face-to-Face with Gustav Klimt. Through January 6, 2013. Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Bourdieu got it right; he got it right a lot earlier than imagined, and for a longer time to come. Arguably Bourdieu had a greater, more lasting influence on the events of May,’68 than a barrelful of Situationists. Some of us were already reading him in the mid-sixties, in particular for his insight that the system of thought and behavior operative in any given field (in the world of art museums, for instance) is also the system of values by which the field defines itself and excludes others. These are the rules that make it possible for the producers and consumers of Culture to participate in the Culture Game. By the same token, to recognize the existence of these rules (as opposed to just playing by them as if the values they embodied were universal) is to strike at the heart of positivist ideology, with its assumption that its own rules are the only, the universal ones. Bourdieu provides a sociological application of Wittgenstein’s philosophical argument about Spielregeln, “rules of the game” – which, by a commodius vicus of recirculation, brings us back to Vienna, Modernism, and Gustav Klimt, the violer d'amores incarnate.

Right now in Vienna, the most significant artwork on display is a plastic, gold–colored egg that opens up to the figures from Klimt’s painting, The Kiss, rotating to the sound of Elvis singing “I Can’t Help Falling in Love with You.” The piece is proudly, sarcastically displayed in a section of the Klimt retrospective at the Wien Museum on the Karlsplatz. The city of Vienna has made a concerted effort to turn itself into Klimtworld in commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the artist’s birth: at last count there are over ten major exhibitions devoted to Klimt, with a few closed already and a few yet to open.

Collect them all! If you show your Klimtpass at each museum’s admissions desk and get it stamped you are eligible for a prize! Klimtworld attempts to construct a universe of celebrants and believers who are ready to produce [a social network] endowed with meaning and value by reference to the entire tradition which produced their categories of perception and appreciation. Which is Bourdieu’s way of saying that buying stock in Facebook might have been a big mistake: social networks don’t form spontaneously, they’re constructed from within, and to take the work of construction as a given is self-defeating in the long run. Facebook was able to exploit certain fields already structured (college kids looking to get laid); its growth strategy was to parasite other fields; it could not, and will not, create new fields. Most important: fields are constructed by their own participants, through the creation and defense of values that are at once exclusive and inclusive―the "eject" button plays a greater role than the "like" button, as any blogger will attest.

“Consumerism” isn’t about consuming alone, it’s about the belief that specific forms of consumption are fated when in fact they’re constructed. In the consumer’s world of Culture, to “love Art,” means to admire The Kiss; or at least to recognize it; or to be aware that Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I now in New York went for $135 million dollars, hence it must be beautiful, or at least important. Hence, to “love Art” means you’re going to go to Vienna to see the Klimts―a weak syllogism if there ever was.

Under capitalism and its sociological system each field is presented as a given, and self-sufficient to the extent that it operates under the same universal rules as capital itself. And the particular field or art-lovers and tourists corresponds, roughly, to what Noah Horowitz attempted to describe as “Experiential Art:” Art whose central dynamic involves hanging, going to flashy parties, visiting museums or “experiencing” videos or performances―I can’t imagine anyone not on drugs actually watching one of those things. Contrariwise, I can perfectly well imagine “experiencing” Documenta, or the Miami Art Fair; I can even imagine “experiencing” Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, and I imagine others could as well, including Mozart himself: even today, Salzburg and Vienna are crawling with Zopfmänner, young men in Mozart drag hustling tickets; I can't imagine burly, unkempt artists wandering around the Museumquartier in Vienna, hustling folks into the Klimt exhibit there, but perhaps I'm naive. There's something off-putting that survives about Klimt, even after all the appropriate adjustments for the myth of the antisocial artist. Like Freud, Klimt was anti-social, anti-establishment, anti-whatever in ways that are still beyond the acceptable; and as in the case of Freud this may present problems of merchandising that are hard to surmount. The Freud Museum has already thrown out its role and mission as a serious research and information project for a vague, artsy Freud “experience,” but unlike Mozart this hasn’t increased the Freud Museum’s attendance by one iota. Likewise, I suspect that, once you compare the cost of the campaign to make more people come to Vienna to see the Klimts against the income generated by the folks drawn to Vienna by the Klimt Jubilee you’ll be lucky to end up even, except of course that the additional income goes to pay the salaries of folks who dream up these campaigns to begin with. The all-important Productivity Index so loved of global economists has nothing to do with whether workers in a certain country produce more, or better; it means the value assigned to whatever they produce goes up in relationship to what they’re paid; so, for instance, a museum worker is more “productive” if she “produces” more visitors with less, as opposed to producing the kind of visitors that constitute a solid, supportive community for the values that the museum itself promotes and supports—which in the case of Klimt might prove virtually impossible: the “experiencing” that Horowitz defines as an integral, organic part of Contemporary Art is not the experience of the producer of art, it’s the experience of the consumer alone; the art, as has been clear since Warhol, is mere pretext: interchangeable, undefined as Muzak, oceanic as Id.

There is a deeper problem with cultural tourism across Europe right now; come to think of it, there's a deeper problem with the economy as a whole. One can't exactly blame that on Klimt; but one can fairly blame it on those who fantasize that a Klimt restrospective is a sure thing. "I Can't Help Falling in Love with You?" That's what's called Whistling past the Graveyard.

Which brings us back to Klimt. In the imputed graveyard of the first Fin-de-Siècle (the one preceding World War I), Vienna was in competition with Paris and other cities as a Kunststadt, a destination site for cultural tourism, the Abu Dhabi of the day. Klimt is notorious for turning his hairy backside to the type of art career offered by the global cartelization of his day: he began as a Government-sponsored painter for the Ringstrasse (the Champs Élysées of Vienna) and moved, gradually, to something far more complex, a relationship to the body, notably the female body, whose own relationship to culture, the symbolic structuring of the body, remains disturbing to this day. In this, our own neo-liberal Fin-de-Siècle (the one preceding World War III), Vienna continues to play the role of Kunststadt; the cartelization of culture repeats itself; and Klimt can only be integrated into the culture of cartelization by being misread on any number of levels, which it has been the task of cultural historians and curators to do or to resist. In his prose poem L'Étranger Baudelaire is asked by a bourgeois interlocutor what he loves most. Gold, perhaps? —“Je le hais comme vous haïssez Dieu.” So, too, with Klimt: They hate him as they hate Freud.

Gustav Klimt. The Drawings. Through June 10, 2012. Albertina.

Museum directors and curators have something in common with the Habsburg Monarchy: affirmations of legitimacy take precedence over the exercise of authority. Since any attempt to assert oneself against the authority of others leads to catastrophe it’s best to give in, even against one’s own interests, but always with a great display of independence. In Vienna to this day, waiters and museum guards still have a sentimental attachment to Franz-Josef muttonchops.

The first objects to greet you at the Albertina’s now-closed show of Klimt’s drawings are a couple of drafts of designs for banknotes that Klimt produced in 1892. The signage tells you these represent a rare, early instance of Klimt’s rejection by officialdom, as though to remind us that rejecting and being rejected by the big, bad world of officialdom and commerce is a badge of pride the Albertina, too, is ready to assume: like Habsburg emperors and Viennese waiters, the Museum wants to let us know they're doing what’s best for us, they're on the side of Art. By now, To Know What’s Best for All the Rest has become institutionalized on all levels of the Eurozone, not least in the world of Culture. European museums (and the Albertina in particular) have developed their own brand of post-modern Schlamperei, a Schlamperei in reverse (called Ierepmalhcs in certain regions of Östeuropa) where the purpose is to be efficient at all costs, especially at the cost of those values in the name of which one claims to act: pure Art, unbesmirched by Commerce. In the new Eurolandia the original passive-aggressive position, Schlamperei, gives way to Ierepmalhcs, the ultimate in aggressive-passive. Tellingly the Albertina's catalogue has an introduction by James Cuno of the Getty Trust, the man who believes the international looting of artworks is for their own good.

Which brings us back to Klimt. At the Albertina a tour-guide was passionately pronouncing before a couple of Klimt’s drawings: hers was a brilliant demonstration of the terminology and practices of connaisseurship; it was also, as passionate tour-guides tend to be, beside the point. Connaisseurship, the close, formal analysis of drawings, is what the Albertina does naturally, being one of the largest, oldest and best collections of European drawings in the World. Unfortunately, connaisseurship is merely a Hilfswissenschaft, it's only as good as the goals it sets itself, the questions it attempts to answer. For this particular show the curators had chosen to answer pointless questions in order to avoid certain other, all-too-pointed questions about Klimt. The show is structured around the untenable assumption that Klimt’s corpus of drawings as a whole can be classified according to the uses he intended to make of them in larger, more “serious” works like frescos and oil paintings: Klimt, like a good little museum worker, is assumed to have been goal-oriented, and most of the drawings in most of the rooms here are arranged around their imagined end-point: Portrait of Frau Y, Beethoven Frieze, etc. Klimt was a brilliant draughstman; he was also a hugely prolific one. One visitor described how his studio was stacked with drawings piled higher than a man’s head. Since there are no reproductions of the finished works in the Albertina's show it’s difficult to determine how the drawings relate to them, and in in many cases it’s a stretch to believe there’s any connection at all. Even in the catalog these connections remain unconvincing, no matter how aggressively pursued.

What emerges from this display is in contradiction with much that Klimt stood, for, or more accurately, lay down for, or maybe that for which he swung from the Jugendstil chandeliers. "I am not interested in myself as a 'subject' for painting," Klimt said, "but rather in others, above all in femaleness.[weibliches]." Femaleness or females? It's an open question for a Symbolist: Klimt was very interested in females, especially of the naked variety; especially in their personal parts; often when abovementioned females were creatively engaged with their personal parts. He may have left as many as fourteen illegitimate children, four of whom are acknowledged. Art as transgression, no doubt; but it's not the kind of transgression that makes for good PR these days.

In 1917, a year before Klimt's death, the Russian critic Victor Shklovsky wrote an article that outwardly presents itself as a critique of Symbolist theories of art, but in its depth is remarkably close to Klimt's own procedures. The article, "Art as Technique," introduced the concept of Alienation Effect, which Bertolt Brecht was to pick up through Tretyakov in Moscow in 1935. The "alienation" sought by Klimt in his drawings is closer to Shklovsky's conception than Brecht's: "The process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged." For Klimt as in Shklovsky the social dimension of the reception of an image is delayed in favor of what might be called its organic, its corporal dimension. "I am not interested in myself as a 'subject' for painting:" After all, the relationship to one’s self is culturally defined, it’s an intellectual construct with its own history. It's the relationship to others that's organic: “Après tout le corps se définit par rapport aux autres, le moi, depuis Descartes, non.”

Sadists, as is generally accepted, are folks who wish to delay the actual, sexual act as long as possible. Klimt wants to prolong the raw act of perception. He is not a visual sadist, as is often feared: he's sadistically visual. Put another way, his sadism is directed toward the market; the process of drawing becomes in Klimt a form of self-directed alienation from the finished, social product, the process of delaying "publication" becomes a form of visuality in and for itself. The undeniable tension in Klimt’s work derives from the tension between his private experience of bodies and his projected experience of the public experience of his art: between a world of working-class producers that includes the world of his models and lovers, and the unattainable world of upper-class consumers.

A contemporary commented of Klimt’s models that they had more personality in their butts than most society women had in their faces. For Klimt, the relationship to the naked body is the organic, the primary one, prior to mediation by the relationship with the culture of clothes and upper-class consumption. His drawings are a quiet conspiracy among producers that the consumer enters at her own risk. As Elvis would say: “Fools rush in,” etc.

Klimt. The Wien Museum Collection. Through September 16, 2012. Wien Museum Karlsplatz.

The Wien Museum claims its own Klimtcollection is “the biggest and most varied in the world;” their Summer Klimtshow is certainly not the biggest, but it aims to be inclusive, or at least varied: it includes a fair number of Klimt’s early paintings and designs; there are 400 drawings by Klimt himself as well posters by Klimt, poster designs by Klimt, paintings by Klimt, and a separate display of recent graphic design that invokes and exploits a certain Klimtitude, not to mention the egg that plays Elvis.

Inclusive no doubt, but coherent? The Wien Museum is not, properly speaking, an art museum, its full title is “Historical Museum of the City of Vienna;” its mission is to present artifacts, not art-historical narratives; and the curators proudly proclaim their indifference to questions of aesthetic quality by plastering most of the four hundred drawings in serial rows up to the ceiling.

All the same, there is a curatorial subconscious at work: this show is one of three current Klimt shows in Vienna structured around Emilie Flöge, Klimt’s sister-in-law, who is usually described as Klimt’s “Muse,” a coy curator’s way of saying that Flöge may have been the only woman Klimt did not envision as a crotch with a body attached. There’s a persistent belief that The Kiss “really” represents Gustav and Emilie hooking up, which only reveals the dialectical incompetence of critics, curators, and the amateur art public: everywhere there’s a forlorn hope The Kiss (and Emilie) can save Klimt from his true, Victorian and politically incorrect self. (To quote a famous movie line, “Do you think you could be friends with a…. girl?”) To content oneself with the merely biographic aspects of the relationship is to forever push to the back-burner the very real question, “what was the intellectual back-and-forth between Flöge’s work as a fashion designer, and Klimt’s as an artist?" The Wien Museum recently sponsored a lecture on Klimt entitled “Women of Yesterday?” followed by a discussion asking the burning question, “How antimodern is Klimt’s image of women?” The press release goes on to describe how the women in Klimt’s pictures were thought to be “lifeless,” which reminds me of Félix Fénéon’s famous quip when confronted by a furious bourgeois in front of a Matisse: “Would you sleep with such a woman, Monsieur?” —“I never sleep with women a quarter-of-an-inch thick.” Only within a positivist culture like ours, the culture of a Gombrich or Popper, a culture where the very possibility of representation as a critique of representation is suppressed, only in such a culture could that kind of question be raised.

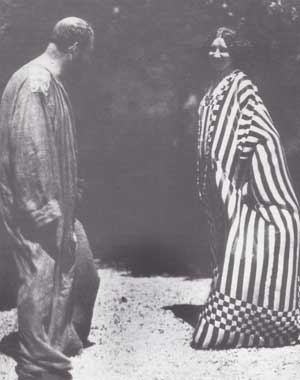

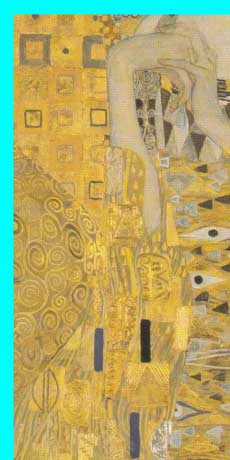

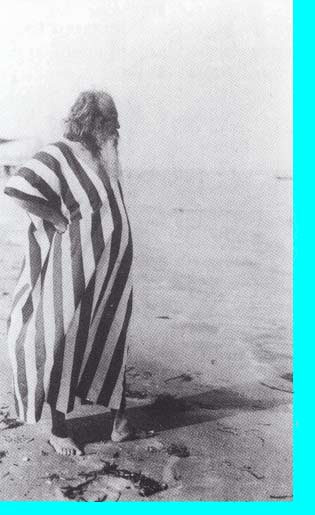

There’s a famous photograph—it’s included in this show: Klimt and Flöge facing one another as in a contra danse, Klimt in his ballooning studio frock (there’s a similar frock in the show), Flöge in a ballooning dress of her own design, of a type that was meant to free women from corsets. It’s a charade in the Victorian sense: the staging of a riddle. Dancing, but upright, not touching in space, clothed, the male representational artist face-to-face with the female fashion designer. Plus, the acknowledged point of corsets was to restrict and define the female figure, a subject for the male gaze, etc. etc. But then, those are the series of markers that define the antitheses that Klimt navigates in his art: upright/lying down, touched/untouched, clothed/unclothed, hiding/revealing, decorative/representational, surface/volume, male presence/absence, self-gratification vs the gratification of the viewer. Much of this can be inferred in Klimt’s magisterial portrait of Emilie, 1902, the highlight of this show. It has to be seen in person: the decorative gold patterning, increasing as the eye moves up her dress, pulls the surface of the painting away from Emilie’s body, or if you prefer, pushes back at the viewer’s gaze. All of this seems to me far more interesting than the question, “utrum copularetur: ” maybe Klimt and I need to get our priorities straight.

Shklovsky, in his 1917 critique, complained that Symbolism in art was an attempt to surround the objects represented with the familiarity of symbolic meanings: “We see the object as though it were enveloped in a sack… Habitualisation devours work, clothes, furniture, one's wife…” Klimt, in fact, proceeded in the opposite direction. The Wien Museum presents us with a number of his earliest drawings, under an academic master who had the bright idea of having his students do nude studies after children rather than adults in order to break their habit of turning to internalized canons of proportions. In his nudes and drawings Klimt pursued this practice of willed de-familiarization, not so different perhaps from Lacan’s idea of the Uncanny; which is to say that Klimt’s conceived of his drawing practice as a pre-symbolic behavior, a movement from Nature to Culture, bodies to clothes, femaleness as bodily function to femaleness as cultural function. (A few years later in Vienna, Melanie Klein was to argue that it was through symbolization that women were able to acquire autonomy and self-identity within a patriarchal culture.)

Shklovsky, in his 1917 critique, complained that Symbolism in art was an attempt to surround the objects represented with the familiarity of symbolic meanings: “We see the object as though it were enveloped in a sack… Habitualisation devours work, clothes, furniture, one's wife…” Klimt, in fact, proceeded in the opposite direction. The Wien Museum presents us with a number of his earliest drawings, under an academic master who had the bright idea of having his students do nude studies after children rather than adults in order to break their habit of turning to internalized canons of proportions. In his nudes and drawings Klimt pursued this practice of willed de-familiarization, not so different perhaps from Lacan’s idea of the Uncanny; which is to say that Klimt’s conceived of his drawing practice as a pre-symbolic behavior, a movement from Nature to Culture, bodies to clothes, femaleness as bodily function to femaleness as cultural function. (A few years later in Vienna, Melanie Klein was to argue that it was through symbolization that women were able to acquire autonomy and self-identity within a patriarchal culture.)  Perhaps the most interesting drawing in this show displays two versions of a model’s hand. One is as close as possible to a life-study; the other takes the same gesture and attempts to reduce it to its affective context. Perhaps, rather than a failed Symbolist, Klimt was a very successful artist of the Baroque. Read your Foucault: he used visual data the way seventeenth-century scientists did, as tools for the classification and integration of data, except it was data of another type. The schemes he used, like those used by seventeenth-century scholars, may seem a bit antiquated today; I'm not quite as eager to see them, or Klimt, as an evolutionary dead-end for Modernism. Klimt got schorskied. We’ve all been schorskied at one time or another.

Perhaps the most interesting drawing in this show displays two versions of a model’s hand. One is as close as possible to a life-study; the other takes the same gesture and attempts to reduce it to its affective context. Perhaps, rather than a failed Symbolist, Klimt was a very successful artist of the Baroque. Read your Foucault: he used visual data the way seventeenth-century scientists did, as tools for the classification and integration of data, except it was data of another type. The schemes he used, like those used by seventeenth-century scholars, may seem a bit antiquated today; I'm not quite as eager to see them, or Klimt, as an evolutionary dead-end for Modernism. Klimt got schorskied. We’ve all been schorskied at one time or another.

IV) Emilie Flöge's Collection of Textile Samples. Through October 14, 2012. Volkskundemuseum.

To schorske, verb [after Carl Schorske, hist.]: to deny legitimacy to anything related to Viennese thought or culture under pretense that it represents the “failure of liberal rationalism.” Ex: “Freud represents the failure of liberal rationalism;” “Klimt embodies the failure of liberal rationalism,” usw. This puts the organizers of this year’s Klimt  Extravaganza in a difficult position since their job is to bring in tourists: the failures of liberalism aren’t much of a turn-on these days. Klimt the Decadent has a certain box-office draw, of course— there’s a dreadful B-movie starring John Malkovich; but Klimt the failure? Klimt the also-ran in the horse-race of Modernity?

Extravaganza in a difficult position since their job is to bring in tourists: the failures of liberalism aren’t much of a turn-on these days. Klimt the Decadent has a certain box-office draw, of course— there’s a dreadful B-movie starring John Malkovich; but Klimt the failure? Klimt the also-ran in the horse-race of Modernity?

The best response so far comes in an exhibition in which Klimt’s work does not appear at all; Klimt is barely mentioned except for a short, hard-edged article in the catalogue. This show reintroduces the stone that the builders of art-historical narrative forgot, or conveniently ignore. It’s about Emilie Flöge’s collection of textile samples, most of them Slovak textiles, though a few are unattributed and others appear to be Jugendstil creations. Flöge used her collection in very practical ways, even exploited it: some pieces were put on display in her chic couture shop in Vienna, others were cut up or handed to the seamstresses; the catalog includes a snapshot of Flöge wearing one of those liberated, uncorseted shifts with Slovak embroidery running down the front.

This all seems terribly unfair. If Flöge can be said to have exploited the creations of anonymous rural workers why not make a similar accusation against Klimt who after all exploited any number of women, and is therefore assumed to have exploited Flöge herself? The difference between Klimt’s drawing practice and his painting practice (as far as they concern the human figure) lies in Klimt’s use of decorative patterns to “clothe” his models, whether they be allegorical figures or posed portraits. The difference between Klimt’s relationship with Emilie and his relationship with almost every other woman, likewise, lies in Klimt’s recognition of Emilie as within the circle of those who read, as opposed to those who are read.

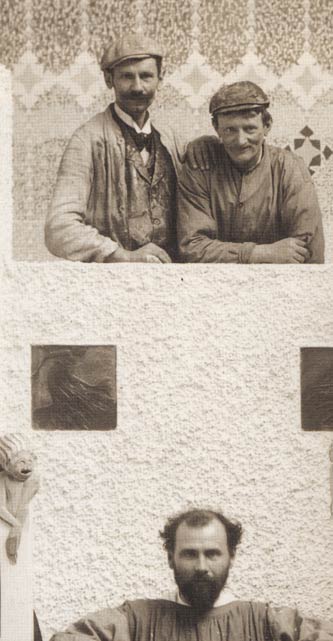

One might object that comparing Klimt’s private affairs with his intellectual affair with Flöge is like comparing apples and oranges. Well, apples and oranges have a dialectic, too. (Synthesis: they’re both fruit.) The two photographs shown above (of Klimt and his workmen, and of Klimt and Emilie dancing), are by Moritz Nähr, who was very much a part of the Viennese bohemian milieu. Such photographs are not the simple presentations of truth as the positivist naïvely assumes photographs to be, but specific narratives about truth involving class, gender, and what a Jugendstil photographer thought gender and class relationships ought to be. Klimt and Emily shared an outlook with Nähr and others, they played their specific roles as interpreters within this group―this “field,” Bourdieu would say. Such roles involve a certain tolerance of sexual experimentation: the one indication of Emilie’s assent and knowledge of Klimt’s sexual activities is a cryptic reference to “adventures” in one of the many postcards that passed between them. In any case, Klimt’s brother Ernst had been briefly married to Emily’s sister, who was a co-owner of the fashion salon Flöge Sisters, along with Emilie herself. At Ernst's death Klimt became the legal male representative for the Flöge Family. Klimt's alliance with the family was a big step upward into the petite bourgeoisie. The first rule of bourgeois rationalism is, “Don’t sleep with your business partner.” Second rule is, “Don’t make a pass at your sister-in-law.”

One might object that comparing Klimt’s private affairs with his intellectual affair with Flöge is like comparing apples and oranges. Well, apples and oranges have a dialectic, too. (Synthesis: they’re both fruit.) The two photographs shown above (of Klimt and his workmen, and of Klimt and Emilie dancing), are by Moritz Nähr, who was very much a part of the Viennese bohemian milieu. Such photographs are not the simple presentations of truth as the positivist naïvely assumes photographs to be, but specific narratives about truth involving class, gender, and what a Jugendstil photographer thought gender and class relationships ought to be. Klimt and Emily shared an outlook with Nähr and others, they played their specific roles as interpreters within this group―this “field,” Bourdieu would say. Such roles involve a certain tolerance of sexual experimentation: the one indication of Emilie’s assent and knowledge of Klimt’s sexual activities is a cryptic reference to “adventures” in one of the many postcards that passed between them. In any case, Klimt’s brother Ernst had been briefly married to Emily’s sister, who was a co-owner of the fashion salon Flöge Sisters, along with Emilie herself. At Ernst's death Klimt became the legal male representative for the Flöge Family. Klimt's alliance with the family was a big step upward into the petite bourgeoisie. The first rule of bourgeois rationalism is, “Don’t sleep with your business partner.” Second rule is, “Don’t make a pass at your sister-in-law.”

One of the more common reactions to the Flöge exhibition has been, “At last, a show where one can enjoy looking at the objects without thinking about them.” And the various samples of needlework are, indeed, gorgeous in themselves. The alternative to pure contemplation, unfortunately, is as inescapable as it’s unpleasant to the contemporary curatorial mind: "The delight in the moment and the gay façade becomes an excuse for absolving the [viewer] from the thought of the whole." (Adorno.) Adorno cut his first philosophical teeth in direct contact with Vienna's cultural machinery. Klimt's vice and virtue is, that he must forever disappoint that machinery.

There can be no doubt that decorative patterns, whether Slovak or Egyptian or anything else, concealed meanings for Klimt: more accurately, that they were meant to convey symbolic meanings. (The young Adolph Gottlieb must have learned from him.) In Klimt these meanings are not made present within the “objectively” rendered yet imaginary three-dimensional space of his sitter’s bodies, but on the surface of the canvas: they are the meanings of the observer. Klimt’s contemporary Marcel Proust wrote that the beauty of sensations lies in front of objects, the beauty of ideas lies behind them. Klimt draws meanings outward from the depth of the canvas to its surface; this puts him on a collision course with the Kantian idealizing narrative of Modernity and so-called Postmodernity, in which ideas hide behind images or objects—“reference” something or other, to the point where everything about the art object falls away except its supposed essence, its referentiality. Klimt and his contemporaries studied the Viennese art historian Alois Riegl and his theory of Formwollen: the idea that form in art could be historically subjective and might be determined by ethnicity, which is not so much a theory as a basic observation of the existence of national or historic styles. Contrary to Schorske, Klimt does not “embody” the failure of rationalism: he takes up a certain form of subjectivity with a whoop and a yell. Unfortunately, in Vienna ideas about historical subjectivity in general could easily lead from “ethnicity” to “race.” There is a series of German words whose sense was made to slide in that direction: Volk, Boden, Stamm, Rasse, Blut: People, Soil, Roots, Race, Blood. It's unfortunate that Klimt’s subjective conception of the meaning of these images (and Flöge’s as well, perhaps) has become a minefield in which today’s curators dare not tread. Adorno once wrote, “The Sociology of Knowledge erects DP camps for intellectuals where they may forget where they have been.” Klimt makes it hard for heterosexual men or Europeans to forget where they have been; we ought to be grateful.

V) 150 Years of Gustav Klimt. July 12, 2012-June 1, 2013. Schloss Belvedere.

V) 150 Years of Gustav Klimt. July 12, 2012-June 1, 2013. Schloss Belvedere.

Goethe once wrote of a great man that in his presence "one doesn't learn something; one becomes something." This is only half true of the Klimt exhibition at Schloss Belvedere in Vienna: one doesn't learn bopkis about Klimt; one quickly becomes annoyed. The exhibition's a perfect success, and a perfect failure: a perfect realization of the neo-liberal, mass-culture fantasy that the dumbing down of Art is the only way to get the Mahsses into the museum―the "cultural cretinism" of capital, as Eagleton calls it, and none-too-successful at that: True, the Belvedere's a bit more crowded than most museums in Vienna these days, but certainly not overcrowded, and certainly no more crowded than it could have been, minus the mendacity.

As to the perfect failure: this is the worst-curated show I've ever seen.

"Seen" may be too kind a word. The windows in the galleries are shuttered, and the curator relies on overhead artificial lighting that shines a) onto the paintings and b) into the visitors' eyes. And since The Kiss is heavily gilded the curator has placed glare-flee glass to compensate. The gilding on Klimt's paintings is one reason among many they have to be seen in person: for the shifting play of light. Here they're made to look like large-scale versions of the cheap reproductions in the gift-shop, as in one of those Broadway musicals where every effect or intonation is calculated to sound like the Original Cast Recording. This show even has its glaze-eyes teenage girls sitting transfixed; and the signage is designed to accomodate their supposedly delicate sensitivities to the point of falsification, as with the claim that Klimt's relationship with Emilie Flöge, his life-long partner, was "platonic." The walls are decorated with art-historical Wankerei like this: "The strikingly anthropomorphic form of the Sunflower can be interpreted as Emilie Flöge in a rational dress." Sure, and the strikingly rude form of my uplifted middle finger can be interpreted as an appropriate response, with far more justification. This show's the visual equivalent of chicklit: call it Klimtschickporn.

Back in 1919 in Vienna, a newly empowered Socialist government desperate to rescue the tourist industry sponsored a performance of Schönberg's demanding Gurrelieder in one of the major theaters; a performance of Schubert in the popular amusement park, the Prater; a perfomance of Beethoven's Missa Solemnis by a worker's chorus in a working-class neighborhood church. Today, to rescue the faltering tourist industry the neo-liberals stage a patronizing, dumb-down show like this for the benefit of the middle classes they despise. Can't wait for it all to end.

VI) Against Klimt. Nuda Veritas and her Defender Hermann Bahr. Through October 29, 2012. Österreichisches Theatermuseum.

VI) Against Klimt. Nuda Veritas and her Defender Hermann Bahr. Through October 29, 2012. Österreichisches Theatermuseum.

The snobs are waiting 'til autumn to succumb on schedule to whatever Klimt-fever Mr. Bahr has planned; and in the interval between ecstasies, to show their indifference to the work of excellent artists that fills the spring exhibitions. Karl Kraus.

You have to hand it to the Theater Museum: The quote above is posted at the entrance to the exhibition that's supposed to demonstrate

VII) Face-to-Face with Gustav Klimt. Through January 6, 2013. Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Bahr is irrelevant to Klimt's art the way most of art historical writing is irrelevant to Vienna, and for similar reasons: it's becoming progressively clear that Vienna never was the "modernist" city Bahr hoped it would become after picking up his talking points in Paris. Vienna was already, and still is, postmodern, as even a glance at its faux-rococo streets will tell you. To find the pre & post-modern Klimt go to the Kunsthistoriches Museum, the major traditional art museum, where Klimt had his first establishment success in 1891 by painting the arches on the second floor in the officially-approved style of "Historicismus." The most remarkable of the lot is the figure (female, natch) of Old Italian Art, meaning Pre-Raphelite; meaning Klimt borrowed from Burne-Jones but spread the figure in a flattened, decorative way; it's like being present at the creation of Jugendstil, which is really a form of late Baroque. Or early Art Nouveau, same difference. Even Bahr knew that.

VIII) Without Klimt. Gustav Klimt and the Künstlerhaus. Künstlerhaus. Through September 2, 2012.

Vienna's Künstlerhaus reminds me of the Art Students League in New York: hardly cutting-edge, but damn, the heart is in the right place. Like the Art Students League it's a nineteenth century artist's association known mostly for the fact that Gustav Klimt broke angrily with it in 1897, and went on to found the Vienna Secession whose wondrous exhibition hall still stands a hundred yards away and a hundred years ahead. All the same, what's old-fashioned about the Secession Movement in Germany and Austria isn't necessarily stylistic: it's the transition from a State-sponsored to a privately-sponsored "free" market. From a political and economic point of view the "revolutionary" posturing of a Klimt or a Schiele is a throwback to the posture of an earlier French generation: that of Baudelaire and the Impressionists of 1874. "Uncompromising" is supposed to be a virtue in Art, except when one's found to be uncompromising in the wrong direction.

As I bought my ticket the salesperson kindly warned me that the Klimt show didn't actually have any pictures by Klimt. It's uncompromising in its own way: a tightly organized display from the Künstlerhaus archives, mostly involved with Klimt's breakaway move, and somewhat concerned with justifying the Künstlerhaus itself: for instance, there are long lists of women artists affiliated (informally, of course) with the organisation.

Most interesting, most challenging and revealing, is a display tucked in a corner of a back room, a few mementos of the Nazi-sponsored Klimt Retrospective, in 1943, which included a number of confiscated pieces. As the curator suggests, the Nazis were the first happy-face fascists:

Ich bin der Geist der stets sagt Ja! For the Nazis of 1943 as for the neo-liberals of 2012, the point of Art was to be relentlessly upbeat. (What Stalingrad was to the Nazis, the Crash of 2008 may well turn out to be for neo-liberalism; some 80,000 Austrian foot soldiers died at Stalingrad.) On display, also, a facsimile of the Nazi exhibition's catalog, with a three-page introduction by the art historian Fritz Novotny; and what's striking about that is, how uncompromising Novotny chose to be: with the exception of two expressions that might, at a stretch, sound like Nazisprache, there's not a mention of Race, Blood, Soil, or any of the other buzz-words he was expected to bring up. (One of these two expressions is the word revolutionary.) And I wonder, fifty years from now, how much neo-liberal drivel will be found in the archives of the various exhibitions of the Klimt Jubilee of 2012; how many misuses of the word revolutionary; how much mitmachen and kowtowing. On the whole, and with the obvious exceptions that I've indicated above, I think my friends, the curators and art historians and museum personnel of Vienna, will have something to be proud of.

- PW.

[6/12/2012 through 8/14/2012; last revised 2/6/2013]

What kind of arrogance is that? – DM, Daily Kos.

You must be referring to the passage where I commend the art historian Fritz Novotny for standing up to the Nazis by refusing to be upbeat about Art, and about Klimt in particular. Perhaps you are unaware that the Nazis abolished the profession of Art Critic: reviews in the Reich were to be consistently optimistic and encouraging. – PW. [9/27/2012]