Review: The Radical Camera. New York’s Photo League, 1936-1951.

New York: Jewish Museum, November 4, 2011-March 25, 2012; Columbus, Ohio: Columbus Museum of Art, April 19-September 9, 2012; San Francisco: Contemporary Jewish Museum, October 11, 2012-January 21, 2013; West Palm Beach: Norton Museum of Art, February 9-April 21, 2013.

Catalog: $50.00 (Paperback), available from Powell's, a union bookstore.

I)

In 1910 Dr. Julius Tandler was elected to a Professorship at the University of Vienna—he would eventually become world-famous as an expert on Public Health; but in 1910 the local press decided to point out the really important fact: that Tandler was a Jew; in fact, “more of a Jew than an anatomist.”

The Radical Camera is one of the finest displays of twentieth-century photography I can recall; except that the curators have chosen the occasion to point out the really important fact, to them: Berenice Abbott, Weegee, Aaron Siskind, Ruth Orkin and other major American photographers of the twentieth century were, thank heaven, more photographer than brainwashed Commie dupe.

There doesn’t seem to be a single major American photographer of the ‘thirties and 'forties who wasn’t associated in one way or another with the Photo League, a small, loose association of photographers headed by Sid Grossman, himself an artist of considerable skill. The League was an offshoot of the Worker’s International Relief (Internazionale Arbeiter Hilfe, or I.A.H.), the left-wing organization founded and run by Willi Münzenberg, a brilliant media organizer from Germany who in 1934 had come to the United States to help set up various American progressive groups. In 1947 the US attorney general issued a list of organizations deemed to be “totalitarian, fascist, Communist, or subversive:” the Photo League was on it. Then in 1949 a certain Angela Calomiris came in from the darkroom, announcing that the League was a Communist front, with Sid Grossman as the point man. The League closed in 1951.

Franz W. Seiwert, Support the I. A. H., 1924. Linocut. From the Isotype collection of Otto Neurath. (See discussion, below.)

As the saying goes, “Where there are two American Communists there are three FBI informers.” The catalog includes research into the FBI’s files on Grossman and the Photo League; but as anyone knows who’s dealt with the archives, there’s another, circumstantial story: the FBI’s war against “reds” was so widespread, scattershot, manipulative and inclusive, that the question “who was a Communist,” dutifully asked and tremblingly sidestepped in the catalog, is moot: “Communist” meant “socialist,” “Socialist,” “social-democrat,” “leftie,” “red,” “homosexual,” “n*-lover,” "union supporter," “New-Dealer,” as it still does in any number of university departments today. One German emigré commented that after 1933 politically naive Americans were apt to characterize their own, often vaguely progressive political positions as "communist" and "pro-Russia," far more so than those Party members who later on were to enlist as repentant witnesses during the McCarthy Era. As for Münzenberg, like many members of the KPD, the German Communist Party, he tried to keep some distance between himself and the Comintern, the Russian organization charged with coordinating the international revolutionary movement; the Nazi takeover in Germany considerably weakened the KPD and strenghthened the Comintern, and Münzenberg led a desperate drive to organize an international front against fascism while attempting to prevent it from becoming a tool of the Russian Communists in Spain and elsewhere; in the process he tried to reconstitute outside of Germany the "Rote Konzern," his network of progressive journals and cultural associations that had been affiliated with the IAH. In 1940, shortly after the Nazi invasion, Münzenberg’s body was discovered in a forest in France; most likely he had been garroted by agents of Stalin.[see Gruber 1965a; Dugrand & Laurent 2008]

II)All of which is incidental—incidental, that is, to what the curators think “good” photography should be: at the Jewish Museum, visitors are greeted by a weasel quote from Beaumont Newhall, quondam head of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art, claiming that at the Photo League “There was almost a sense of desperation in the desire to convey sociological import;” as if conveying sociological import was a particularly hopeless kind of enterprise, at odds with what would come naturally to real photographers and artists: say, pictures of kittens. In 1937 Newhall curated a standard-setting exhibition of photography for the Museum of Modern Art from which the Photo League was absent, much as Henry-Russell Hitchcock had expunged the architecture of Red Vienna from the MoMA's standard-setting exhibition of Twentieth-Century Architecture in 1932. Being an artist or an architect and socially conscious could only be a hindrance on one’s aesthetic sensibilities, just as being a Jew in Vienna could only be a hindrance to achieving anything based on merit, not money. Just as orthodox Marxists invent an “imputed class consciousness” to describe what the Working Class should be thinking if it were to think the way Marxists think it should, so, too, the curators have invented an “imputed aesthetics” which the photographers in this show are assumed to have followed, whatever their pretense at being socially conscious. After all, being an artist or an architect and socially conscious can only be a hindrance to success, not so, Professor?

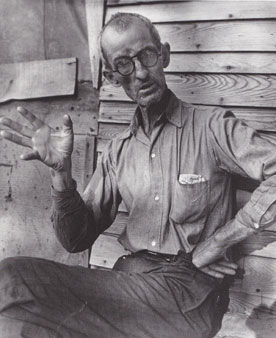

All the same, the stunning beauty of these photographs is attributable to a specific “socialist” aesthetic which is not at all at odds with their aesthetic qualities but an integral and irreplaceable part of it. Take Sid Grossman’s portrait, Henry Modgilin, Community Camp, Oklahoma (1940)—doesn't every photographer wish she had?  At a glance the viewer recognizes the antitype of the soulful closeups of sharecroppers’s faces beloved of Walker Evans in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: Henry Modgilin is caught in mid-discussion, equal emphasis on his gesturing hands, his face, his posture, his background, which is to say that each aspect is presented as an ideograph to be deciphered in its own right. A few blocks uptown from the Photo League studio in Manhattan, the art historian Erwin Panofsky was lecturing about the late medieval genre of the Andachtsbild, the Image of Devotion: a figure of Christ, for instance, that the viewer was encouraged to confront head-on and eye-to-eye, in the same manner that a visitor at the Museum of Modern Art (say, for its Family of Man show of photographs in 1955) would eventually be called on to confront herself in the act of confronting some image of a worker or a homeless person or African, her undifferentiating gaze a token of the “authenticity” of her own experience.

At a glance the viewer recognizes the antitype of the soulful closeups of sharecroppers’s faces beloved of Walker Evans in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: Henry Modgilin is caught in mid-discussion, equal emphasis on his gesturing hands, his face, his posture, his background, which is to say that each aspect is presented as an ideograph to be deciphered in its own right. A few blocks uptown from the Photo League studio in Manhattan, the art historian Erwin Panofsky was lecturing about the late medieval genre of the Andachtsbild, the Image of Devotion: a figure of Christ, for instance, that the viewer was encouraged to confront head-on and eye-to-eye, in the same manner that a visitor at the Museum of Modern Art (say, for its Family of Man show of photographs in 1955) would eventually be called on to confront herself in the act of confronting some image of a worker or a homeless person or African, her undifferentiating gaze a token of the “authenticity” of her own experience.

This is precisely what Henry Modgilin is not; and the curators are bothered enough to mention in the accompanying signage that Grossman “accentuated the tones in order to dramatize” the various parts of the picture. In case you didn’t know, photographers choose certain apertures in order to get certain effects; they crop and adjust photographs; they manipulate the light so that the viewer’s gaze is directed towards certain parts of the image and away from others. That’s what photographers do. It’s also what sociologists and anthropologists and social workers and maybe even community organizers do when dealing with a client, a tribe, a target population: they separate out the various elements that they hope will reveal the meaningful aspects of the subject and his environment. In this case, it appears, Sid Grossman has used a certain amount of solarization to delineate and separate out each part of the composition. To the curators this comes across as some evil Communist plot; or maybe some evil Socialist plot. Or Muslim plot. Whatever.

One constant of almost every photograph in this show is the careful sectioning of the image, often within a grid that implies the use of a Golden Ratio. The grid suggests the inspiration of the Mexican Revolution rather than the Russian: the Mexican Minister of Education, José Vasconcelos, had heavily promoted the Golden Ratio as a system of harmonious proportions among the State-sponsored muralists—even young campesinos were taught to draw this way in rural schools; and Paul Strand, one of the founders of the League, spent considerable time in Mexico, even working for the Government there. Mexican rationalist mysticism shares this pattern with Russian Constructivism and to a certain extent with Bauhaus practices: all tend to use images of rationalization as an educational tool to glorify rationalization. Contrariwise, League artists do not use form for form’s sake, but rather in order to organize an understanding shared between the photographer-sociologist and the viewer. Jack Manning’s Elks Parade (1938) is a superb example, a highlight of a four-year League project called Harlem Document:

A parade is being viewed in Harlem; the marchers are not seen, only the backs of the row of watchers on the street and beyond them, facing us, the faces and bodies of Harlem residents watching from the fire escapes and rooftops of the buildings whose single façade provides the visual and social framework of their activity. Manning's picture provides a remarkable balance of individual and group, with the group itself defining the environment that defines it in turn. This photograph reminds me of an early text of Walter Benjamin, on a visit to Naples, writing of “porosity,” the supremely political interpenetration of interior and exterior lives. It’s also remarkably non-judgmental, as good sociology, or social work, or community organizing should be. And it sends the curators into a tizzy of accusations, with the claim that the Photo League’s Harlem project “portrayed the African-American community in a negative light,” that the League photographers (who were mostly Jewish) ignored the African-American photographers who’d been documenting Harlem life for decades, and so forth. There was a time not long ago when any suggestion that “the Jews are trying to take over Harlem,” even photographically, would have raised objections amounting to hysteria from the very same folks who are now pushing the same line at the Jewish Museum, except they substitute “reds” for “Jews,” which is an irony to the nth degree since the Communist Party was extremely active in Harlem as in other black neighborhoods in the ‘thirties and ‘forties. (The Communists ran a black as a vice-presidential candidate as early as 1931; and Vito Marcantonio, who represented East Harlem in Congress, openly welcomed their support.) The Photo League’s take on Harlem could only seem negative to the kinds of folks who think renting your apartment or not owning a car is a badge of shame to begin with; as the critic for the New York Times explains, the image of people sitting or standing or fire escapes to watch a parade is really about “dangerous living conditions.” (There should be a law requiring curators and Times reporters to be residents of the planet they cover.) The German critic Helmut Lethen has argued that certain forms of "progressive" realism of the 'thirties exhibited a paralyzing Opferperspektive (victim's viewpoint) that discouraged political involvement under pretense of sympathy. This is hardly the Harlem that the Photo League showed, and certainly not the Harlem they would have been inclined to show if they'd been the Commie front group they're suspected of being: starting with the first Five-Year plan in 1932, the principles of socialist realism required the artist to represent objectively and in a positive light the "abolition of class differences" in rural Russia. Likewise, one may imagine the purpose of a white liberal casting a positive light on the inhabitants of Harlem to be the abolition of racial differences. The "functional" purpose of the Photo League's work in Harlem was not to show pity but solidarity – solidarity with the people of Harlem, as opposed to solidarity with its real-estate opportunities. At any rate the Photo League’s reportage formed the visual background for a much more grim analysis in the mass-media magazine, Look, in 1940, written by a black sociologist. Three years later the Harlem Riots broke out. Must have been them Comm-U-nist agimataters...

III)

There is an unbridgeable gap between the kind of sociological-aesthetic reportage practiced at the Photo League and the sociological illustration that the curators imagine it to be, as demonstrated by a series of photographs by Lewis Hine and Paul Strand that are intended to introduce this exhibition:

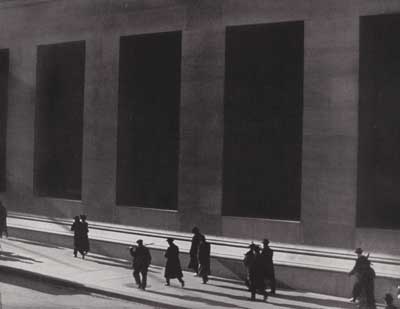

Strand's Wall Street, New York of 1915 reads like the illustration to a sociology textbook, by Georg Simmel no doubt: anomie, blah, blah; Modernity, blah, blah; the individual in the big bad city a mere cypher of his social class, blaaah. Hine had studied simmelian Sociology at the University of Chicago; Simmelianism was a stock-in-trade of the progressive liberal clique at the New Republic. Whatever the considerable formal qualities of this image, they're served up on the side: Strand's image is a sociological Andachtsbild.

In contrast the approach of Sid Grossman to Henry Modgilin is reminiscent of the visual sociology of Otto Neurath, the Viennese polymath who had a lasting influence on graphic design, urban design, signage, museology and a few other areas as well. Neurath, who was an active member of the Vienna Circle of philosophers, had taken up Wittgenstein's problematics of Vorstellung: a representation can never duplicate the presence of the thing it represents; rather, it's a pretext for "language games" that involve the viewer in its own interpretation. From this Neurath developed the concept of the isotype:

A basic piece of information can be reduced to a simple image (as Strand had done); but the image itself can, and must, be subsequently open to visual manipulation and distortion in order to convey to the viewer its more specific cognitive uses—Kant's a-priori synthetic judgments are an illusion. The Isotype System was widely used to convey complex statistics; it was widely known and used in America from the late 'twenties on; but there was (and is) no reason not to apply it to more “aesthetic” purposes, specifically to purposes that bring together plastic harmony and cognitive coherence: as Neurath put it, "Everything that serves to visualize social connections through images ultimately serves humanity." The process is before all dialectical, involving the viewer in the "unpacking" of a complex piece of visual information into smaller elements, either conflicting or congruent, or both. Neurath and the Photo League are indebted to Constructivist visual strategies such as those proposed by Sergei Eisenstein in "The Cinematographic Principle and the Ideogram." The Soviet filmmaker sees parallels between the organization of visual information in a film shot, and the hierarchy of procedures for reading a Chinese written character or a Japanese mask: a visual object or sign, "objective" to the viewer's first glance, is modified by a copulative that indicates the ways in which it is to be read:

This shift that the photographer enforces on the viewer, from mere visual apprehension to the questioning of the material apprehended, is the strategy that Walter Benjamin found to be suppressed in the practices of positivist photography. In "The Author as Producer" he proposed a "materialist pedagogy," demanding that artists "take up photography," thus "transcending the barrier between writing and image." This strategy is repeatedly taken up among the photographers of the Photo League; not that they'd read Benjamin, or that Benjamin somehow had described the eternal metaphysical essential functions of all photographic practices which photographers would more or less spontaneously follow. To those who recognize only positivism as a legitimate epistemology (meaning: to the vast majority of American art critics and curators) the only valid approach to be imputed to a photographer, even a politically committed photographer, is Positivism; therefore they cannot but fail to see that the artists of the Photo League followed an aesthetic movement that was built on the rejection of Positivism, and specifically on the rejection of that variety of aesthetic positivism known in the 'twenties and early 'thirties as Neue Sachlichkeit. Siegfried Kracauer, the German sociologist and theoretician of Photography and Film, put his rejection thus:

In the early 'thirties such theories were in the air. Benjamin himself had borrowed a good deal of his argument from the Constructivist László Moholy-Nagy, whose work and theories on montage were well-known at the Photo League, and who himself had developed them alongside the Russian Proletkult movement. Both Moholy-Nagy and Proletkult were indebted to Ernst Mach, the Viennese philosopher and physicist so hated by Lenin, so influential on left-leaning theoreticians of art in the early nineteen-twenties—including Neurath: The Vienna Circle was formally registered as the Ernst Mach Society. To quote A. A. Bogdanov, a founder of Proletkult: “Art organizes social experience by means of live images not only in the sphere of knowledge but also in the sphere of feelings and aspirations.” Not only in the sphere of feelings, but in the sphere of knowledge, since the point, following Kant's intellectual foil, the philosopher David Hume, was to refashion the relationship of knowledge and affect.

IV)

There ought to be a sign over the door of the School of Benjamin reading, "LET NO ONE ENTER WHO DOESN'T KNOW DIALECTICS." There isn't; but if there were, Weegee, that strange photographer of crime scenes and a Photo League associate, would walk in with a swagger. Consider the following image:

Now, consider its title: New York Patrolman George Scharnikow Who Saved Little Baby.

Marx once wrote of the French novelist Eugene Sue, that he exemplified the "most wretched offal of socialist literature:" he was like a fifth-rate painter who needed to put a label on everything he painted before the viewer could understand it. Weegee conscientiously sets before us the most wretched offal of capitalist journalism, offal that discloses itself, not in its positivist matter-of-factness, but in the relationship that the viewer is forced to establish towards matter-of-factness itself. Benjamin again: "What we require of the photographer is the ability to give his picture a caption that wrenches it from modish commerce and gives it a revolutionary use value." It is not enough for photographic practice to bend towards theory: it's the theory that needs to be bent by practice, or what's the point of organizing an exhibition like this one?

In his autobiography, The Bread of Time, the poet-laureate Philip Levine writes:

In those days independent working Americans were proud of being red, which did not mean membership in the Communist Party: it merely meant struggling with the common people against the exploiters. No matter what you've been told to the contrary, we reds knew the difference between the totalitarian, brainwashed CP members, the professional Communists, and ourselves, the reds who wanted not to be encumbered with another hierarchy of bosses.

It’s a Mozart and Salieri thing, or a Benjamin and Hannah Arendt thing, which amounts to the same: most higher-up cultural workers in America – the academics, the composers-in-residence, the curators – can bear the thought of someone being more accomplished than they; what they can’t bear's the thought that someone might accomplish so much without making the compromises that they themselves pretend they’ve had no choice but to make: there are, and have been, a few artists and scholars whose success has not depended on sleeping with Nazis. And isn’t that the usual rationalization for Global Capitalism? “Yes, capitalism destroys lives and cultures, but isn’t it’s worth it in the long run?” “Yes, every monument of culture is also a monument of barbarism, but egad, Sir, look at those swirling impastos!” And what if one could create a monument of culture after all that was not, for once, a monument to barbarism? Photograph and be photographed; to hell with hierarchies.

3/16/2012; last revised 4/12/2013.

- PW.