WOID XXI-48

MIZ LINDA UP IN THE BIG HOUSE

On October 29 my old teacher, Linda Nochlin, passed away. On the

same day or thereabouts, I signed a petition among art workers that

began:

I signed this letter in memory of Linda Nochlin and much of what she stood for. I, too, have held my tongue.

It must have been the first or second week of Nochlin’s seminar. The class was invited to attend a panel involving another of her art historian friends, Eunice Lipton, the kind of invitation a graduate student is not at liberty to refuse. Lipton had just published a book revealing to an unsuspecting world that Degas was a misogynist—weak tea, indeed. Perhaps this explains why Lipton devoted much of her time to denouncing the “Tootsie Syndrome,” meaning those men who might get the idea they, too, could get in on that Feminism thing. Flectere si nequeo superos, Acheronta movebo: it occurred to me in passing that if all men were truly wired to act like men then they might as well give up and do as Nature and Eunice told them, but what kind of man would sink so low? Back then no one had ever heard of a Trump voter.

Nochlin, I soon realized, was on the same page when it came to this type of verbal assault. It must have been the second or third week when she read to the assembled seminar her own contribution to a catalogue of Courbet. Actually her text had nothing to do with Courbet, it was a riff on Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’Herbe in which the roles were switched so that instead of a single naked figure there was a serving of beefcake while Nochlin and her friends pranced around in crinolines. Not only inappropriate in a scholarly publication, not only offensive, but also lousy art history since it happily ignored the biting irony at the bottom of all of Manet’s paintings. Gender discrimination, Nochlin was telling us, was tickety-boo so long as it came from herself and her colleagues.

In the following years I had the occasion to find out how tickety-boo that was. The CUNY Graduate Center at that time, and the Art History Department in particular, were cesspools of low-level harassment directed at men—or rather, at male graduate students. If you think actors and museum workers are in a vulnerable position within the power structure, take a look at graduate students and I should know, I’ve been active in all three professions. At the Graduate Center it was impossible to get any kind of mentoring, or even to be kept informed of job opportunities; it was hard at times to ask for something as simple as a reading list without being abused by a department secretary with pointed sexist comments. In fact it was nearly impossible to graduate because most of the faculty simply refused to advise candidates. I gave up going to the Employment Office after the head brought me into her office, demanded I close the door (a violation of harassment policies in itself), and then started to threaten me for supposed sexist crimes. Fortunately, she soon realized she’d overshot her mark and it was I who had good cause for a grievance against her. We both agreed to let the issue drop.

The whole situation culminated with a scene in Nochlin’s class, when one of her students—not among the swiftest, I recall—publicly accused me of insulting her by daring to address a female artist, while Linda happily looked on. This was followed shortly thereafter by a phone call from one of Nochlin’s colleagues and protégés so inappropriate that I was left with two choices: either to file suit or get myself out of there with my PhD as fast as I could. I’m glad to say I took the second option. Nochlin must have realized she was getting herself in dangerous territory, because shortly thereafter she published an essay of some sort that was all about the arrogant Marxist graduate student coming into her office in his leather jacket. (I was rather proud of that jacket, actually.)

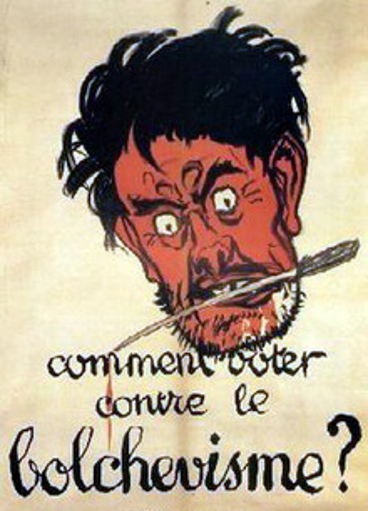

In America it’s always safest to slander someone as a Communist. Nochlin’s actions reminded me of another situation I witnessed at the time of the Vietnam War in which that other great feminist heroine, Grace Paley, frenziedly laid plans to have a group of male Marxist students expelled illegally from the college where, she believed, male students did not belong to begin with. I’ve occasionally wondered why a certain generation of feminists should be so obsessed with Marxism, but then traditionally there’s been two types of feminism, going back to the nineteenth century. The one is deeply egalitarian, the other, quite the reverse. Communists today serve the same purpose for women like Nochlin that black men served for the wives of plantation owners in the Old South: a fantasized threat that justifies their own supremacy. White women, as Pierre Bourdieu has pointed out, are the “dominated segment of the dominant class.” Like the rest of us they have to decide which side they want to serve. Or, as the art-worker’s petition put it,

Clara Zetkin and la Duchesse d’Uzès are not sisters under the skin.

I might have let the whole story lie forgotten, except for what we’re seeing today in the theater, the universities and elsewhere. In America at least businesses and institutions are required to have rigorous guidelines in place against harassment and discrimination. The fact that a business or institution can be shown to have tolerated a “hostile workplace environmentˮ can be enough to decide a civil lawsuit against them, and that’s often the only weapon available to the oppressed. Imagine how different the situation would be today if such guidelines had been applied consistently and fairly; if unions had been in place from the git-go; or if those unions that are in place, like the Screen Actors Guild in America, had stood for zero tolerance and 100% openness to grievance, which they have not. Nochlin and her peers within the Union, the Administration and the higher-level faculty not only tolerated a “hostile workplace environment:” they fostered it, and this has nothing to do with feminism, merely with their willing participation in an oppressive system of exploitation. (For the record, Nochlin did attempt to exploit my research; I suspect she turned against me after I explained to her that to do so she would have to totally transform her own methodology; or perhaps when I went over her head and proposed a paper at a conference organized by one of her colleagues. I didn’t think much about it at the time, because, hey, that’s how graduate students are treated, male or female.)

One British parliamentarian put it best:

At the CUNY Graduate Center as elsewhere the unions, Administration and some among the senior faculty looked the other way, not because it was males alone who were harassed—it wasn’t—but because it profited the institution and its top staff to keep the low-level employees, the part-timers, the assistants, in a continuous position of vulnerability. Any stick will do to beat a dog.

I’m told a large percentage of white American males

when polled respond that they feel themselves to be victims of

discrimination. I suspect, if asked, those same respondents would agree

that in America everybody is discriminated against, even more so if

they’re black, or female or Other, but that’s the question never asked,

because it’s the question that unites instead of dividing. Because they

systematically undermined the ability of institutions to address issues

of inequality and bias, because they directly benefited from inequality

and bias, because the ruled by dividing, not uniting,

Linda Nochlin and her peers must bear some part of the responsibility

for the present, horrifying reality. As we Commies like to say, “An

injury to one is an injury to all.”

PW

November 12, 2017