WOID XXI-24

Venice Biennale, May 9 through November 22, 2015. http://labiennale.org

“All the World’s Futures.” That’s the title of this year’s Biennale in Venice. That's futures, as in assets (artworks, say), whose worth the investor (or viewer) is asked to validate in anticipation of their actual performance—“painting breaking through to its own future,” as Michael Fried might put it. And what kind of performance is that? What kind of investor’s asked to fork out upwards of 25 euros to be done the favor of being allowed to do the validating? Such questions are not asked sufficiently of futures of any kind, let alone of artworks and their audience. You’d think an exhibition that involved a live reading of Karl Marx could do better; at the very least you’d expect an exhibition like that to try; or at least try not to obfuscate the issue.

At this Biennale as usual the prize for disambiguation goes to Hans Haacke, who gives a reprise of his 1970 work, MoMA Poll. The original version asked visitors to decide (by paper ballot, how quaint) if they supported the Rockefellers’ own support of the Vietnam War. This year in Venice, Haacke asks visitors to fill out an electronic questionnaire about themselves and their socio-economic status before they can view the results. Haacke collaborated with Pierre Bourdieu a few years ago, and that’s strengthened his grasp of socio-cultural capital; his questionnaire surely sharpened my own: of all the participants in Haacke’s new quiz, 57% have no direct involvement with art; 44% expect to spend less than 1,000 euros on art in their lifetime; 46% earn less than 20,000 per year and a very high percentage have an advanced degree of one kind or another. This audience (excuse me: consumer base) is not simply different from your usual Art Basel mix of wealthy gamblers, clueless collectors and upsucking artists: it’s an audience at odds with it, if not antagonistic. The same polarization that now divides the world into financial winners and losers has begun to affect the world of Art as well. Whether the class most present at the Biennale has the will or the energy to embrace those forms of culture that are truly its own, is an open question: this is a class that comes to Culture with the same fractured consciousness Walter Benjamin found in Baudelaire:

As Adrian Searle, artshole #2 at the Guardian, put it, “Whether Karl Marx matters to most of the people here... I’m not sure, but it certainly seems strange with all these guy’s yachts outside.” At 20,000 per year it matters, believe me.

“Each generation must,” As Frantz Fanon put it, “out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfill it, or betray it.” Visitors to the Biennale, like Baudelaire’s bourgeoisie, are not buyers of artfutures (or pork bellies, as it happens); rather, they’re the mechanism by which artfutures are validated. Their historic mission is to confront the commodification of their own attempts to accumulate cultural capital—by visiting the Biennale, for instance. Their task is to discover their own solidarity in production, not consumption—a prise de conscience, Bourdieu would call it—even as their own productive labor is turned into a highly abstracted, nearly ungraspable form of production.

The exhibitions spaces proper for “All the World’s Future” are assigned by this year’s designated curator, but the model is similar: Okwui Enwezor has “conceded” to the galleries a space to promote their artist-clients, in exchange for promoting artworks that address the topic he believes (and I think, rightly so) to be of greatest interest to the imputed audience: the visitors’ relationship to labor—or at the very least, their relationship to what they believe to be the labor of others. The artworks on display are not about selling: very few of them could qualify as formalist, as pure raw material claiming a “natural” rather than a culturally-determined valuation, like pork-bellies; their valuation for the purpose of the accumulation of symbolic capital depends on their “message” which, as determined by the curator, centers on labor and the need for social solidarity, or its futility: the need to relate to, and understand, one’s own relationship to labor.

Most Sentimental in Show goes to Hiwa K’s The Bell, a plodding video spell-out of Friedrich Schiller’s Song of the Bell, a nineteenth century hymn to heroic labor and to workers’ solidarity with their bosses, one of the most popular works in German literature. (The artist lives in Berlin.) Far more cutting, if equally nostalgic, the polymorphous efforts by the Englishman Jeremy Deller and a number of collaborators to bring out the history of British labor struggles in the nineteenth century, often with original materials. The nineteenth-century broadsides are beautiful, but the only work I saw that directly connected the Heroic Age to the present was the banner by Ed Hall, Hello Today You Have Day Off, referring at once to traditional union banners and to the text message a day-worker might receive in any number of maquiladoras today.

Of course every call to action, as it passes from the rulers downward, must also involve a call to inaction, it’s what Fox News calls “Fair and Balanced.” Pino Pascali’s Canon (“Cannone Semovente”), dating from 1965 has been resurrected: it reminds me of the helicopter helpfully placed over the stairwell of the Rockefeller’s Museum of Modern Art during the Vietnam Era, ‘case you got any ideas. Then there is Runo Lagomarsino’s “Following the Light of the Sun I only discovered the Ground,” a rare piece of neo-liberal propaganda art, involving a projection of images of the building of some type of Soviet-Era sculptural monstrosity. It’s unusual, but hardly surprising, if one understands how reactionary Brazilian contemporary art is, and has been. My fave, though, is the following signage: “[Taryn] Simon’s work examines the stagecraft of power—how it is created, performed, marketed and maintained. Sponsored by Gagosian Gallery.” The title of the piece is: “Paperwork, and the Will of Capital.” So Capital has a Will of its own? I thought it was the people who had wills… Christian Boltanski’s there with “L’Homme qui Tousse,” a rip-off in theme and spirit of Bruce Nauman’s equally sadistic work. The usual consolatory fantasies of the power of labor are put in the ring against those dystopian fantasies of individual powerlessness that play such an important role in the armory of Fascism:

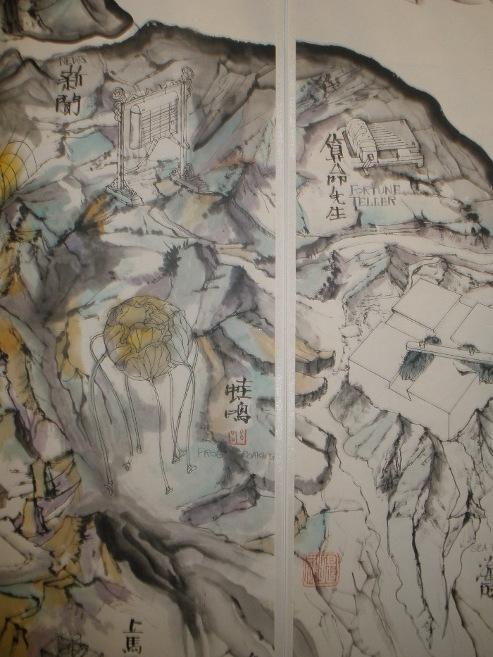

The only work I saw that transcended these false antinomies was the installation by Qiu Zhijie, a superb unfolding of Chinese forms of visual knowledge in all their contradictions, East-West and otherwise. Qiu Zhijie fulfills Adorno’s dictum that there are works of art whose dialectic operates at such great depth that they are dispensed from answering the question of what they’re about, politically or otherwise. That the installation was deemed “totally incomprehensible” by Number Two Artshole should be commendation enough.

I’m happy to report that my friends at Gulf Labor conducted a series of panels on the exploitation of workers at the futures-museums in Abu Dhabi, but I’m still not clear why one panel was entitled, “Who needs Museums and Biennales?” The better question, it seems, would be: “Who needs institutions whose structures parallel other structures of repression in a society at large? And how can a museum function in a way that’s different from the functioning of an office?” I had the opportunity to ask the question at the desks that somehow formed a part of Adrian Piper’s prize-winning installation; that is, I had the opportunity to ask it and discuss it with Giulia Natalia Salamon, who was also part of Professor Piper’s installation—she plays the part of an employee fielding questions from "customers." My thought was, that neither Piper nor the others could evade the Marxist truism that capitalism is a relationship among people that masks itself as a relationship among things, which things happen on occasion to be called artwork, and supposedly to have a will, for instance a will to “break through to their own future” like a shipment of pork bellies; that there was no more urgent task than to demystify that relationship; and that, in my opinion, the artists at the Biennale (Piper first among them) had signally failed to do so, witness the situation in which Ms. Giulia was, in effect, incorporated into Piper’s installation, one object in a relationship with another, just as surely as Piper’s work was a call to commodify the visitor’s response—including mine, which Ms. Giulia duly recorded. Piper’s work is symmetrical to Haacke’s: Hacke’s is intended to allow visitors to gain control over the product of their labor (the visit to the galleries), and Piper’s commodifies the visitor’s response by taking it down and re-using it. I’m sure Ms. Giulia has her own ideas about this but you’ll have to ask her yourself, I wouldn’t want to get her in trouble with her boss...

10/09/2015