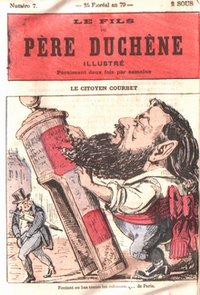

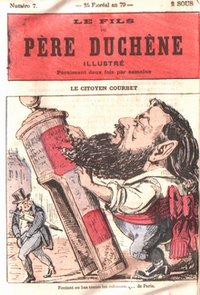

Caricature from the Commune: Courbet, wearing his red deputy's sash, evicts a bourgeois from the public latrine that was the Vendôme Column.

Caricature from the Commune: Courbet, wearing his red deputy's sash, evicts a bourgeois from the public latrine that was the Vendôme Column. WOID XVIII-44, 47. Bonjour, Comrade Courbet!

Gustave Courbet

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Through May 18

Courbet was a "Republican?" Golly, geez, it must be true because the New York Times just said so. Courbet, the great French nineteenth-century painter and political activist, the man who sold to the ruling class and yet refused to sell out, the man who was almost shot for his participation in the Paris Commune, would have voted for John McCain according to Roberta Smith, the Times' art critic.

Well, the Times never lies. Well, not exactly; they just kind of don't quite give you the whole truth. Late in 1851 when a Parisian journal denounced Courbet as a "socialist painter," Courbet responded:

I am strong enough to act alone ... Monsieur Garcin calls me the socialist painter; I gladly accept that description; I am not only a socialist, but also a democrat and republican, in short a supporter of all that the revolution stands for, and first and foremost I am a realist.

Back then a "republican" (as opposed to a "Republican" nowadays), meant somebody who supported the Second Republic, the democratic government brought to power by the working class in the Revolution of 1848. Whatever Courbet's words might have meant in 1851, they took on another meaning two weeks later when the Republic was brought down by Napoleon III. After that, anyone who thought of himself as a republican (like Courbet's friend Manet), would be simply placing himself among the enemies of the Regime.

Courbet, unlike Manet, didn't keep his head down. Armed with the prestige he'd earned under the Republic (notably the medal that allowed him to show his paintings in the State-sponsored "Salon" without a jury's approval), Courbet embarked on an eighteen-year career of painterly and political resistance, with considerable help from his friends and fellow-troublemakers: the second lie from the Times (the more egregious one), is the description of Courbet as a "narcissistic loner." Narcissistic, maybe, but Courbet had plenty of friends, just not the Times' kind of people.

Among them was the anarchist legend Pierre-Paul Proudhon - there's a painting of him in the show. Of course, say the art historians, that means Courbet can't have been a "real" activist since Marx himself dismissed Proudhon in The Poverty of Philosophy. This didn't stop Courbet, or Proudhon's followers, from joining the Paris Commune of 1871: Courbet himself was elected to the governing body of the Commune and served on its committee on public education, as well as working to reorganize the museums, art schools and exhibitions on democratic lines, which kind of conflicts with Wikipedia's assertion that he saved the museums from "looting mobs." Oh, well.

Caricature from the Commune: Courbet, wearing his red deputy's sash, evicts a bourgeois from the public latrine that was the Vendôme Column.

Caricature from the Commune: Courbet, wearing his red deputy's sash, evicts a bourgeois from the public latrine that was the Vendôme Column.

Unless they mean the looting mobs of right-wing troops that stormed Paris, shooting some 30,000 men, women and children and shipping thousands more to the colonies. Courbet was captured, imprisoned, and eventually charged with destroying the hideous Vendôme Column, for which he was fined an enormous sum. Courbet fled to Switzerland where, for once, he might have been described as being a loner, except he seems to have had plenty of friends helping him churn out all those chocolate-box paintings that bear his signature. A troublemaker to the end, he died on December 31, 1877 - or maybe January 1, 1878. Nobody knows. Not even the New York Times. Especially not the New York Times.

II)

It’s not as if there were no mention of Courbet’s politics in the show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art - why there’s a whole room at the end, devoted to Courbet’s paintings after his arrest and imprisonment following the fall of the Commune: typical revolutionary paintings of fish, and of fruit. What the signage doesn’t bother telling you, is that a strict censorship was applied to the visual arts after the bloody butchery. Courbet painted a dead trout with the fishing line still caught in its mouth, and at the bottom, in Latin : In vinculis faciebat, meaning: "produced in captivity." Then there’s a pile of battered apples in a pile under a dark hill – “Little red guys with holes in them,” as someone once described them. At the Met, the explanation for these paintings is that of Klaus Herding, one of a number of Courbet scholars implicitly quoted in this unfocused, unthinking show: “It is only rarely possible to discern a directly political iconography in [Courbet's] pictures.” The only politics involved is the hidden kind.

Courbet meets his patron and client Alfred Bruyas as one free man meets another. On the left, a servant shows the humility of the enslaved. Courbet has shown himself as a Compagnon, an independent traveling apprentice.

And that’s a problem but it’s not Courbet’s: if it’s “direct political” symbolism you’re looking for you’re apt to miss the point of what’s political about Courbet. The question whether Courbet painted political themes is a question asked by liberal-lefty art historians whose own politics is always outside themselves: their politics are always in the content of what they themselves stand back and describe, never in their own actions. Linda Nochlin, the feminist, has even argued for a feminist “reading” of Courbet’s art, as if his obnoxiously sexist close-up of a vulva – possibly the first beaver shot in the history of painting – wasn’t really who Courbet was, a revolutionary and a sexist: as if this image was merely about society, and not about Courbet. Nochlin, who herself is haunted by fears of Marxists turning up in her office wearing leather jackets, would rather imagine Courbet as a feminist than a leftist. She might have asked Courbet, not in order to believe him, mind, but out of common courtesy.

But then Courbet wasn’t a Marxist anyhow, he was a follower of Proudhon and his Proudhonian anarchism was consistent from start to end of his career: until the Impressionists came along in 1874 the radical thing to do if you were a radical artist was to push for a free market at a time when Great Art was supposed to be approved and patronized by the State. One Marxist art historian has complained that Courbet was a petit-bourgeois painter painting for the petite bourgeoisie, and that’s quite correct. But then the Commune itself was mostly made up, not of factory workers, but of the small shopkeepers and independent craftspeople who constituted a majority of the French proletariat into the twentieth century. Painting for the petit bourgeois could well, under proper conditions, become a radical endeavor.

Courbet consistently pushed his anarchist-libertarian message in the face of authority. At a time when elderly French gentlemen would turn up at the Salons, the Government-supported art shows, with magnifying glasses to check that every detail in each painting was “correct,” Courbet painted in a rough-hewn way that called forth the viewer’s own subjectivity – a slap in the face of those painters who produced works that only survived through the dictates of the official market. Courbet was a master-extrovert who loved to play the part of the painter-peasant, rough and direct in his painting as in his life. Once, he and his students took on the painter Couture and his students in a Paris café, with each master haranguing the other from a tabletop. Courbet was the model of what one frustrated factory capitalist called Le Sublime: the skilled worker who turns in good work – work good enough that he can tell the boss to take a flyer, and the boss knows it, and gnashes his teeth and puts up with it. Hey, it's a living...

This only places Courbet in the much broader category of non-academic painters, those who “don’t wear clean underwear” as one critic put it: the Barbizon painters of nature and the others. The difference is, that Courbet’s painting manner stood explicitly for the liberation of the worker: by claiming the right to an unalienated way of painting, Courbet claimed the right to unalienated labor for all workers. When the critics complained that Courbet painted no better than a bricklayer with his trowel, Courbet proudly took this up as a badge of pride. If his painting of a trout is “revolutionary” it’s not because the style is innovative or forward-looking, it’s for the massive, rough blocks of color that seem slapped on. Like Jackson Pollock, Courbet says you, too, can do this. All you need is a trowel and a dream.

Which is to say that in Courbet, as in all great painters of the nineteenth century, painting style and content alike were iconographic: how Courbet painted had an implicit political meaning as much, if not more, than what he painted. In front of a Courbet the liberal bourgeoisie and liberal art historians are confronted with the hideous possibility that real meanings are hidden from them, not in the way a secret is hidden from the all-powerful Master, but the way a thing escapes the Master because he/she does not understand the language of reality, which happens to be the language of the worker, the worker-painter who makes the True Sign of the Universe. “Courbet’s blues?” said André Breton. “They’re the blues of the Parisian sky the day the Vendôme Column fell.”